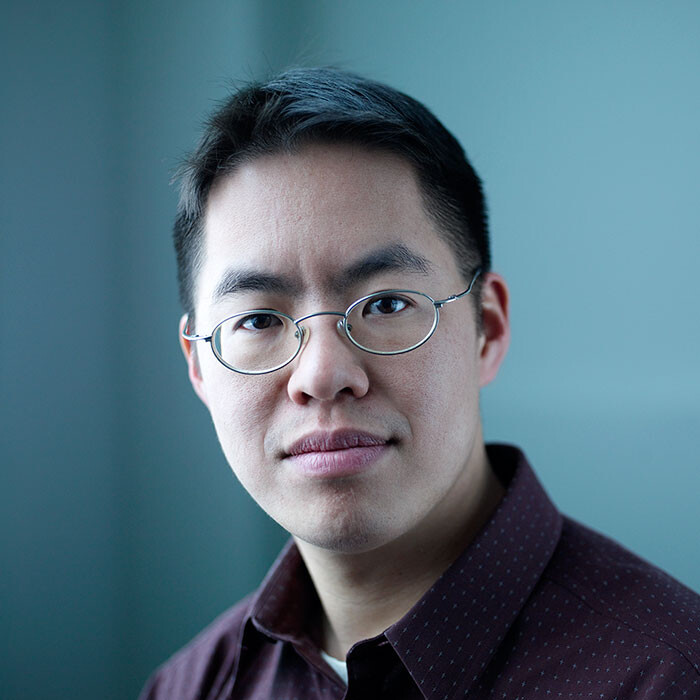

Dr. Vincent Lam, MD ’99

Dr. Vincent Lam (MD ’99) is a physician and award-winning writer of fiction. His first book, Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures, won the 2006 Scotiabank Giller Prize, and was adapted for television and broadcast on HBO Canada. His most recent novel, The Headmaster’s Wager, was nominated for the 2014 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. After thirteen years working as an emergency doctor in Toronto East General Hospital, Dr. Lam recently changed his career path to pursue a new passion in addictions medicine.

One of the gifts that medicine gives to people who train in it is an opportunity to reflect on yourself, your own strengths and weaknesses, and be able to improve not just as a physician, but also as a person.

You’ve been an emergency doctor for thirteen years. What motivated the change in career to addictions medicine?

I desired to have continuity of care with my patients. As an emergency doctor, you’re responsible for everything that’s going on in a very short period of time – everything that’s happening with a patient for the next few hours – but then you never see them again. In addictions medicine, you’re responsible for a smaller range of problems over a longer period of time, which includes physiological as well as psychosocial issues. The field of addictions is not well understood, and even somewhat stigmatized. I view this work as serving an underserved population as I’ve always been interested in underserved populations.

What were some of your career dreams upon graduating from U of T’s Faculty of Medicine?

When I graduated from medical school, I first did a residency in community medicine, which is the training program for public health practitioners. I wanted to be a public health practitioner while working clinically in emergency medicine.

What originally drew me to emergency medicine is the allure of being involved in rapidly evolving situations, and the potential to acquire a broad skill set. I wanted to be part of people’s lives during moments of extremity in a positive way by being able to say, “Whatever happens now, I can stabilize someone, get them safe, and figure out what they need next.” I think emergency doctors are some of the most skilled doctors out there. If you are going to be stuck on a boat drifting at sea, or a desert island, and you can choose one doctor, I would pick an emergency doctor.

How did writing fit into your dreams of medicine?

In addition to wanting to be a community health doctor and an emergency doctor, I also wanted to be a writer. But after I finished my clinical training, I realized that I couldn’t do all three.

In public health, one has long-term, ongoing projects that occupy a lot of time. I thought it might be hard to reconcile this with a career writing fiction, which also involves a commitment to long-term projects and a long trajectory of thought. It seemed that emergency medicine might be compatible with writing because it is sharply focused and delineated in time. You go, you work very intensely, you’re totally consumed, and then you leave. You pass the patients on and you don’t necessarily take that responsibility home with you.

How do you find the time to write?

Most writers will say that finding time is the hardest thing. I think this is especially true for people earning their living by doing something else. It’s not any mystery process, though. You just have to schedule the time, commit to it and do it, which is really tough. Actually, it’s my number one challenge.

What are some of your proudest professional moments?

There are moments in peoples’ lives that become publicly recognizable. If you write a book and win a big prize, it changes how people look at both you and your book. If you are an emergency doctor, and you win a prize, people are amazed by it. That’s what we often think of as achievements, but I’m more interested in doing a really good day’s work right now. If I have a good day of writing, that gives me satisfaction. If I have a good day at my addictions medicine clinic, that gives me satisfaction. But that is more quiet, and it’s not the sort of thing that gets counted in the sphere of public achievements.

What words of wisdom would you like to share with current and future students of the Faculty of Medicine?

One of the gifts that medicine gives to people who train in it is an opportunity to reflect on yourself, your own strengths and weaknesses, and be able to improve not just as a physician, but also as a person. As health care practitioners, we should meditate on how the profession’s proximity to illness and death affects us because one of the traps in medicine is to become blunted and immune to human suffering and human death. But I think the better path to follow is to think about it, reflect upon it, and consider what it means in your own life.

News