A Different Vehicle for Breathing Support in Patients with COVID-19

If you had access to a Ferarri, what use would you have for a Beetle?

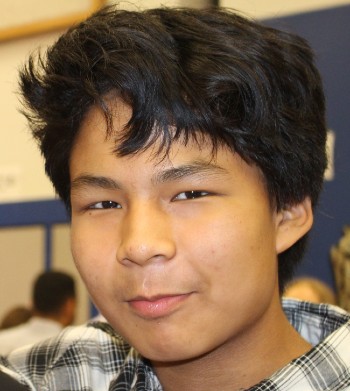

For Paul Dorian, a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, the beauty of the "people's car" lies in its simplicity.

“They can't go as fast as a sports car, but they’re extremely reliable. You could practically fix them with band-aids, paperclips and elastics when they break down and they last nearly forever,” he says.

Like the durable vintage Volkswagens, Dorian says the Oxylator — a handheld emergency device for heart and lung resuscitation — is reliable, compact and easy to use.

And, he says, it may be a useful vehicle for breathing support during a ventilator shortage as COVID-19 cases continue to rise.

"Like a Ferarri, a ventilator is sophisticated, expensive and takes a lot of training to operate,” says Dorian. “But you can teach someone in an hour how to operate an Oxylator. Plus, they’re portable, indestructible and don’t need electricity.”

Dorian, who is also a clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, had previously studied the gas-powered gadgets for use in cardiac arrest.

He reached out to ventilation expert Laurent Brochard, professor of medicine and clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, to test the Oxylator in a bench model that simulates a lung damaged by COVID-19.

The team also tested the machine in an animal model.

“Not only did it work nearly as well as a ventilator, but it turns out that the benefits we suspected, like simplicity, ease of use, reliability, durability and expense were proven,” says Dorian.

According to Dorian, the field devices cost about 50 times less than a ventilator, which can carry a price tag of about $75, 000.

Applying the device for COVID-19 occurred to Dorian while he was behind the wheel of his own vehicle, driving home from Florida last March as the novel coronavirus began to spread globally.

Health officials at the time were warning the number of patients with serious breathing complications could outstrip the supply of ventilators, and hospitals in other countries were overwhelmed by demand for the medical equipment.

A ventilator shortage has not yet materialized in Canada, but it’s still a threat. And Dorian says there’s potential for the devices to be used in remote communities where there aren’t any ventilators. With the help of Art Slutsky, a professor of medicine and surgery, his team is also working to find out whether the Oxylator can deliver ventilation that’s gentle on the lungs.

“When people receive mechanical ventilation from a ventilator over a long period of long time, the act of pushing air into people’s lungs can damage the lungs,” says Dorian. “Because of the way the Oxylator’s technology works, we believe this method may be particularly good at lung-protective ventilation.”

A caregiver such as a nurse, physician, respiratory therapist or ambulance attendant needs to monitor the patient at the bedside during Oxylator use.

There are already about 15,000 of the devices in use around the world, mostly in ambulances, helicopters and military units.

Dorian and his colleagues are now looking at whether the Oxylator would be most helpful to the people who are most sick with COVID-related lung disease, and if they would be useful in healthier patients who need ventilation for other reasons, like recovery from surgery.

The research was supported by the University of Toronto’s COVID-19 Action Fund, St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation and CPR Medical Devices, which makes the Oxylator.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Selenium and Antioxidants: A Powerful Pairing

Peanut butter and jam. Apples and cinnamon. Pancakes and maple syrup. Some things are just better together.

Peanut butter and jam. Apples and cinnamon. Pancakes and maple syrup. Some things are just better together.

Turns out, antioxidants and selenium have a similarly complementary relationship.

Selenium is a nutrient that’s naturally present in the soil and some foods.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of earlier research reveals that people who took antioxidant supplements containing the mineral selenium had a lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality.

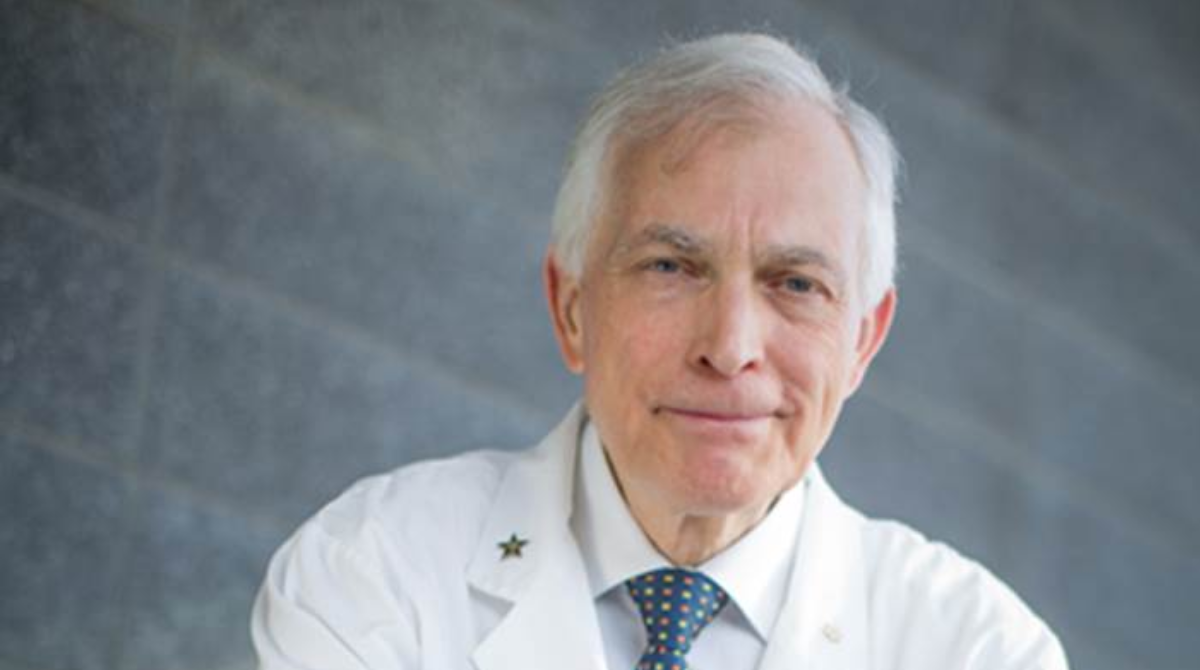

The work was led by David Jenkins and John Sievenpiper, who are both professors of nutritional sciences in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

The paper was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition and examined 43 randomized control trials.

There is longstanding interest among scientists in the role of antioxidants, like beta carotene and vitamins C and E in reducing the risk of many age-related diseases like CVD, diabetes and cancer.

But the trials to this point have been mixed.

In each of the trials the team looked at, participants took oral antioxidant supplements or a placebo for at least 24 weeks.

Each of the supplements consisted of a combination of two or more antioxidants including retinol, beta carotene, selenium, zinc, copper and vitamins A, C and E.

“For supplementation, we found that it depends on what’s in the mixture. Without including selenium, antioxidants didn’t have much benefit. On their own, antioxidants may even do more harm than good,” says Jenkins, who is also part of the Department of Medicine and a clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital. “And selenium by itself does nothing.”

“For supplementation, we found that it depends on what’s in the mixture. Without including selenium, antioxidants didn’t have much benefit. On their own, antioxidants may even do more harm than good,” says Jenkins, who is also part of the Department of Medicine and a clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital. “And selenium by itself does nothing.”

Though some antioxidant supplements and multivitamins already contain the nutrient, it’s important for people to read the labels.

Health Canada says people should consume no more than 400 micrograms of selenium per day from food, water and supplements combined.

The organization regulates selenium levels in food, drugs and natural health products as well as in pesticides, cosmetics and paint.

Taking too much of the mineral can cause problems like stomach disorders, hair loss, or nail deformation.

Though it is rare in North America — where the soil is rich in selenium — being deficient in this essential nutrient can leave people vulnerable to other conditions like Keshan’s disease, a form of cardiomyopathy.

Though the study focused on supplementation, Jenkins says until the long-term effect of selenium on antioxidant supplement use is better understood, eating a balanced diet of antioxidant-rich foods is a good approach.

“If you eat a variety of plant-based foods, like nuts, seeds, and dried legumes such as peas, lentils or beans, you should get what you need. That’s why we keep seeing these kinds of recommendations coming out,” says Jenkins, pointing to the updated Canada’s Food Guide, which promotes eating more fruits, vegetables, whole-grain cereals and plant-based protein.

Jenkins says supplementation may be important in some groups, like marginalized or elderly populations which may lack variety in their diets.

The team plans to further their research by creating a mix of vitamins and nutrients to explore the potential benefits for people with COVID-19. Jenkins says they hope to identify a blend that can help shorten the duration of illness, prevent adverse effects and hospitalization.

“There is evidence that antioxidants vitamin C and zinc help shorten the duration of a common cold, which is a type of coronavirus”, says Jenkins. “That’s why we’re enthusiastic about pushing into this area.”

Professors Jenkins and Sievenpiper have received support from government, non-profit and industry funding sources and been on the speakers’ panel, scientific advisory board and/or received travel support and/or honoraria from companies and industry groups that produce or promote nutritional supplements. Please see the Acknowledgements section at the end of the study for a full list of funding sources and industry connections.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Erin Howe

Making Change: How a Tragic Loss Inspired Two New Awards for Indigenous MD Students

“We are all able to make change. All of us are able to make change.”

As a paediatric infectious, tropical disease and global health specialist, Dr. Anna Banerji (MD’89) has been guided by this philosophy throughout her entire career caring for, researching and advocating on behalf of the world’s most vulnerable children. And, now, two years after the sudden death of her adopted 14-year old Inuk son, Nathan, it’s also something in which she’s found great comfort and healing.

Banerji’s first journey to the Arctic in 1995 changed her career and life trajectory. Since then she has been to the Arctic about 50 times. On one particular trip, an Elder mentioned to Banerji that the community was experiencing a shortage of foster and adoptive families. She replied by sharing her long-standing interest in adopting a child someday.

That someday came nine years later. At the time, Banerji had already been leading research in the Arctic for nearly a decade and had grown especially close to the Inuit communities in Nunavut.

The Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami had just struck and Banerji was preparing to join a Red Cross relief mission to the hardest hit areas. Her phone rang. It was a resident Banerji was supervising who was doing a stint in Iqaluit. In discussion with the Elder, Banerji’s name came up. There was a baby born that morning who needed a home. The Elder told the resident “Dr. Anna always said that she would adopt an Inuk baby.” Was she still interested in adopting?

Banerji meant what she had said nine years earlier and, in fact, had already completed all the requirements for an adoption. When she was called, she instantly agreed to adopt, although she didn’t even know if the baby was a boy or girl or its age.

Banerji saw Nathan for the first time when she was arrived to pick him up from the Arctic. He was four months old. Her almost four-year old daughter was very confused when Banerji showed at the airport up with a baby — telling her friends that her mother bought the child at the airport!

Banerji was overjoyed. But she was also deeply aware of the trust the community was demonstrating in her by placing the infant in her care. While Nathan grew up in Toronto, Banerji worked closely with her peers in the Arcticto help nurture and maintain the boy’s ties to his birth community and family, as well as to his Inuit heritage. She watched him grow up into an exceptionally caring young man, who always placed the needs of others before his own.

“Nathan loved the Arctic,” Banerji says. “We returned often, and he was always welcomed home like a celebrity by his birth family and the wider community. But, as he matured, Nathan started to see the many challenges the community faced. Many Inuit residents, including those to whom he had become close, lived in extreme poverty. He also became aware of the prevalence of substance abuse and youth suicides. It began to weigh on him.”

Banerji believes the crisis point came following the death by suicide of Nathan’s older, 14-year old biological brother.

“Nathan began to deteriorate quickly as he approached his own 14th birthday,” says Banerji. “He shared that he was feeling overwhelming anxiety and depression. We tried to get him help, but kept running into brick walls. The mental health system failed to recognize the inter-generational trauma he was experiencing — trauma that we believe was uniquely informed by his Inuit heritage."

Twelve days after his own 14th birthday, Nathan also died by suicide.

Now, two years after this tragic loss, Banerji is joining several close friends and colleagues in leading two new initiatives that seek to both honour Nathan’s life and contribute to positive change for Indigenous students in the Faculty of Medicine.

The Nathan Banerji-Kearney Award for Indigenous Students is a new needs-based bursary in the MD program. It was established by Banerji’s classmate, to help reduce financial barriers for medical students, and encourage more Indigenous young people to consider medical careers.

To complement this bursary, Banerji and Diana Alli (retired Senior Officer, Service Learning, Community Partnerships, Student Life in the Faculty of Medicine) have also established The Nathan Banerji-Kearney Memorial Award for Indigenous Students. This award will recognize a fourth-year, graduating Indigenous student in the MD program who demonstrates excellence in working with Indigenous communities.

“I believe Nathan’s story is just an example of the much-larger challenges Indigenous peoples have faced and continue to face in Canada,” says Banerji. “By providing these opportunities to Indigenous medical students, we’re taking a small step forward. We need to do better. We can do better and these two awards will help.”

To make a gift in support of The Nathan Banerji-Kearney Memorial Award for Indigenous Students, please visit our Nathan Banerji-Kearney Memorial Award for Indigenous Students or contact Michelle Fong, Senior Development Officer in the Faculty of Medicine at michelley.fong@utoronto.ca

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

Honouring a Beloved Mother through Support for Alzheimer’s Research

More than twenty years after her death from Alzheimer’s disease, Brent Allen’s memories of his mother’s giving nature remain bright. That’s why he chose to establish The Mary Bernice Allen Memorial Fund in her name in the University of Toronto’s Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

More than twenty years after her death from Alzheimer’s disease, Brent Allen’s memories of his mother’s giving nature remain bright. That’s why he chose to establish The Mary Bernice Allen Memorial Fund in her name in the University of Toronto’s Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

“My mother’s whole life was dedicated to caring for others – be it her family, her friends or members of her wider community,” says Allen. “Her experience with Alzheimer’s disease was very challenging, both for her, as well as for us, her family. I know she would be pleased to know that, through this fund’s support for research, she’s helping other people living with the same illness.”

Through his generosity, The Mary Bernice Allen Memorial Fund is helping to provide Alzheimer’s disease researchers with essential resources such as lab supplies and equipment repair.

“The Tanz Centre’s big appeal for me is its focus on research,” says Allen. “So much progress has been made in how we treat Alzheimer’s disease since my mother’s diagnosis in the early 1990s. It’s wonderful to think that this gift could help researchers discover new treatments or even a cure.”

“We’re so grateful for Brent’s support,” says Tanz Centre director, Professor Graham Collingridge. “The funds help us to purchase materials and supplies that are critical fuel for research – allowing us to continue to advance our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease.”

To support Alzheimer’s disease research via the Mary Bernice Allen Memorial Fund, or any other Tanz Centre fund, please visit our online giving page.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

UofTMed Alum: Letting My Inner Voice Speak

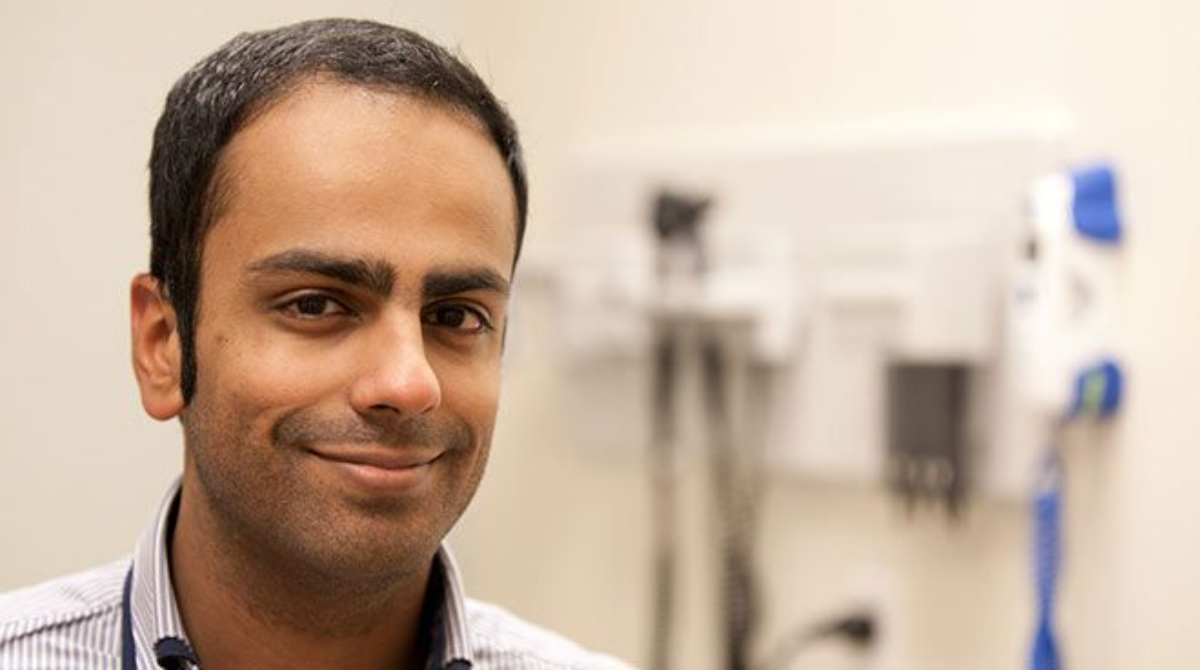

I was fresh into my first few months of my residency training in internal medicine. I had been warned about what to expect: long hours, challenging patient cases, stress. Now it was showtime, and weeks were almost blending into one another.

My days as an undergrad and medical student had been filled with academic research projects, grassroots advocacy campaigns, extracurricular activities, narrative writing and medical education initiatives, all alongside heavy coursework and clinical duties. As I began residency on July 1, I made a conscious decision: I wanted to be the best doctor I could be, and that meant making time on the wards my only priority.

Yet, even though I was doing less with most of my time spent on the wards, the days somehow felt shorter and were finishing faster.

“What moments have stuck with you the most over the last few months?” a mentor asked me in September. It was the first time I had been asked — I had not even stopped to ask myself. I paused briefly, then replied, “I don’t know. There have been a whole lot; yet somehow, I can’t think of one.”

It was not a lack of profound experiences. It was not a lack of incredible clinical learning. It was a lack of hitting pause to let experiences sink in, and remind myself what was valuable to me.

I’ve always been committed to nurturing myself as the kind of physician who puts the values and preferences of my patients first and invests everything I can into their care. But I never accounted for the hidden cost of these commitments: the challenge of holding onto the pieces of me in the process that made me me.

I turned to writing to pull those pieces back together. First just on sticky notes and Microsoft Word documents, then in a journal. I came home every day and put pen to paper, eventful or uneventful. As I wrote, I deconstructed and reconstructed moments in the day I’d tucked away without a second thought — and somehow understood each one better.

I spoke to many colleagues and close friends in those months. Some told me how difficult it was to have less time with family. Others shared how a patient’s death or poor outcome had devastated them. Some others spoke about how they were developing new skills and finally knew they had made the right decision in choosing medicine as a career.

We all had stories — and we wanted to share them.

I decided I would start with me. I began sharing my stories and perspectives online with friends and colleagues through CMAJ Blogs, Healthy Debate, media outlets and other forums. The opportunity to reflect and share was refreshing. The response and shared enthusiasm from colleagues and friends was revitalizing.

At the same time, intriguing cases on the wards raised important clinical questions that captivated my research mind. Interacting with some of the most vulnerable individuals in our societies on the wards fueled a fire to support and lead grassroots advocacy efforts around their healthcare rights. Working alongside inspiring mentors made me immerse myself in understanding different teaching techniques and model the same for my junior trainees. Toronto was filled with opportunities to pursue these passions — I was incredibly fortunate. And as I did, I was reminded: I loved medicine because it is so much more than just the medicine. These parts were just as important to being the doctor I envisioned myself being.

My hours on the ward didn’t change. Yet, days slowed down. The blur gained more clarity. It was showtime.

Fast-forward two years. I am on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic alongside brave colleagues and mentors. I am also a researcher, co-leading rapid international evidence synthesis efforts to impact clinical practice. I am a storyteller, collecting perspectives from colleagues and friends about what matters to them during a time of immense change. I am an advocate, pushing for healthcare access for our society’s most vulnerable in the face of a virus that does not discriminate based on having or not having an OHIP card.

Yet, I am at peace with myself. In the storm of the pandemic, I’m at peace with what I’m doing to lift up my patients and their families. And I am more connected with myself — and others — than ever. This is exactly the kind of doctor I wanted to be.

If there was ever a time to look inwards and reflect, it is challenging times like these ones. If there was ever a time to reflect on your passions and put them into action to make a difference, it is now.

I look back at one of the first pieces I wrote in 2018 as I started residency, titled “Twenty-Six Hour Days”. It is more relevant today than ever, in the face of the pandemic. Let us remember to take care of ourselves as we continue putting our best foot forward to take care of others.

Twenty-Six Hour Days

Twenty-six-hour days

pacing the hospital wards.

Day turns night turns day—

if it weren’t for a momentary glance at the clock,

I wouldn’t know otherwise.

I scribble the letters “AKI”

across the lined A4 sheets in my charts.

My last drink was 12 hours ago.

By some stroke of irony,

it ceases to matter anymore.

The regular family banter and friendly exchange

lights up my phone screen, unanticipated—

unwanted.

I swipe it away quickly without a second glance,

without allowing myself more than a transient thought—

I have no space for this: for me.

I had dreamt about this all my life.

Stethoscope around my neck,

a physician’s ID badge hanging against my chest,

caring for patients.

Was I not living the dream?

I look around me

to find others—my colleagues, my juniors,

toiling through their EMRs and paper charts.

I wonder if they ever glance back and wonder the same:

am I alone in struggling through this?

Can they hear me?

They all seem to fit in the jigsaw of the hospital,

their confident voices drowning me out as I search for mine.

Posterchild for ‘imposter syndrome,’

I wonder if I’m the wrong piece for this puzzle.

I continue my rounds—

patient by patient, room by room,

listening closely to the crackle of drowning lungs,

convincing myself I appreciate the weak double waveform of a neck vein impulse,

poking a tender belly and digging into the intimacies of a relative stranger’s bowel patterns.

Along the way, I console an anxious family member,

hold the hand of a sick patient left in solitude,

explore the delicate prognosis of an end-stage cancer patient,

MSIGECAPS my way into the deepest corners of a struggling patient’s journey.

Is your mood okay?

Are you sleeping okay?

Are you still interested in your hobbies?

Are you feeling guilty?

I look around the room for a moment,

catch my reflection in the window.

I can’t help but wonder:

what would my answers be?

I stop myself short of answering—

I feel guilty for wondering.

Twenty-six-hour days

pacing the hospital wards.

Day turns night turns day.

If it weren’t for just a moment’s reflection

or an occasional external unwanted reminder:

I’d forget about me.

Dr. Arnav Agarwal, MD ’18, is an internal medicine resident. You can read more about COVID-19's long-term impact on health care and health care professionals in the next issue of UofTMed magazine, which will hit inboxes this July. If you'd like to receive a digital copy along with other UofTMed news, please subscribe to the MedEmail mailing list.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Arnav Agarwal

Honouring Impact: The 2020 Dean’s Alumni Awards

U of T Medicine alumni have always been renowned for their contributions to their communities. Today, with the global COVID-19 pandemic shining a spotlight on health and healthcare providers, we are prouder than ever to announce the recipients of the 2020 Dean’s Alumni Awards.

This year’s honoured awardees include a Parkinson’s disease research pioneer, a paediatric social justice advocate, a champion of the homeless, a leading suicide prevention researcher and a home hemodialysis innovator. While their work may be diverse, each shares an important attribute: a commitment to making a difference.

“The five recipients of the 2020 Dean’s Alumni Awards represent the very best of our extraordinary alumni community,” Dean Trevor Young. “Their leadership, service to others and commitment to innovation will positively impact the lives of countless individuals.”

This year, the Faculty of Medicine is honouring:

Dr. Lang is the former President of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society and past Editor of the journal Movement Disorders. He pioneered the use of specific rating scales for a number of neurological movement disorders (including the most commonly used scale for cervical dystonia), advocated for the use of experimental therapeutics in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and was instrumental in changing the way that Parkinson’s disease is evaluated. Dr. Lang established the Pan American Section within the international Movement Disorder Society — uniting clinicians and scientists from the United States, Latin America and South America, and representing those regions in the Society’s programming and outreach. | |

| |

Dr. Dosani founded Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH) — Canada’s first community-based Palliative Care outreach program, aimed at supporting the needs of Toronto’s most vulnerable and marginalized citizens. The street and shelter-based community outreach program aims to meld evidence-based practices from the field of Palliative Care with best practices from inner-city health research, using a supportive and empathic approach. Since its founding in 2014, PEACH has become nationally and internationally recognized with over 350 patients receiving PEACH-style care. As a result of his leadership and advocacy, Dr. Dosani inspired the development of Journey Home Hospice (JHH), a residential hospice that provides high-quality end-of-life care to individuals who have lived along the homeless continuum. | |

Dr. Sinyor is an international leader in suicide research and is at the forefront of shaping suicide prevention at the local, national and international levels. He has advised Canadian media about safe reporting related to suicide, as well as the World Health Organization and Mental Health Commission of Canada on creating guidelines for safely disseminating suicide-related content. Dr. Sinyor has also created workshops for the lay public and educators across Ontario on how to understand mental health, build resilience, and to talk safely about suicide. He is also the creator of a 3-month mental health literacy and skills curriculum for middle school students, which is being used across Ontario and will soon be in use in several countries around the world. | |

Dr. Chan has made globally-recognized contributions to home hemodialysis. He has championed and defined this important therapy, leading and coordinating a large network dedicated to the clinical and basic science aspects of optimal dialysis delivery. He leads an internationally-recognized home dialysis centre of excellence in Toronto and led the development of the UHN-Baxter Home Dialysis Fellowship. Dr. Chan also co-chaired the International Consensus Statement of Innovative Dialysis Therapies and has over 200 highly cited peer-reviewed manuscripts. |

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 award recipients will be formally honoured at the next Dean’s Alumni Awards Reception in Spring 2021.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

Dr. Wayne Carman: Investing in Plastic Surgery Research

Dr. Wayne Carman [BSc ’72, MD ’75, MSc ’79, FRCSC ’82 (Plastic Surgery)] is the former Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at The Scarborough Hospital and also served as the Director of the Scarborough General Hospital Burn Unit. He was President of the Canadian Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (CSAPS) and is the Secretary-Treasurer of the Canadian Association for the Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (CAAASF). He founded and maintains his own private clinic, the Cosmetic Surgery Institute, in midtown Toronto.

Dr. Carman has the distinction of being one of the first people to graduate as a surgeon scientist in the Faculty of Medicine. This fall, Dr. Carman established the endowed Dr. Wayne Carman Surgeon Scientist Trainee Award as a way to both help advance his field and to honour a fulfilling career.

“Let’s face it, economic realities on the academic side always exist — there are never enough resources, so I think if you have the opportunity to mitigate that a little bit, it’s fulfilling… it underscores the commitment I have to furthering plastic surgery research.”

Dr. Wayne Carman [BSc ’72, MD ’75, MSc ’79, FRCSC ’82 (Plastic Surgery)] has had a rewarding career in both the private and community spheres. He enjoys running a private practice and maintains an appointment at the Scarborough Health Network. Dr. Carman recently spoke with Director of Alumni Relations Sara Franca about the field of plastic surgery, his gift to the Department of Surgery — and reflected on some of the more memorable moments of his career.

What made you choose to pursue medicine in school — and what is it about the area of plastic surgery, in particular, that appeals to you?

I knew I wanted to go into medicine, that was an early decision. There are no other medical people in my family, but I liked the idea of it, the scope of it — the problem solving and the personal interaction.

I always leaned toward surgery. I have always been more of a hands-on person, and I felt the manipulative aspect of surgery was appealing — the dexterity and the challenge of the physical part. I then needed to narrow that down, and plastic surgery came into the mix. I felt early on that plastic surgery was one of the more interesting fields. It probably had the most scope for original thought and creativity — we operate on all parts of the body and the problems are frequently unique.

I also recognized many branches of medicine are mainly diagnosis related. This is a valuable aspect of medicine, but in most medical specialties, the greater part of one’s energy is spent determining what is wrong with somebody and treatment often is the lesser part of the exercise. I found plastic surgery to be the exact opposite — the diagnosis is generally obvious — most of your energy is focused on fixing the problem. I felt a clinical field, which placed more emphasis on problem management, would be the most satisfying career choice.

While you were in school, were there any specific colleagues or faculty members who made an impression on you?

I pursued the idea of plastic surgery starting in medical school and met Dr. J. F. (“Jim”) Murray (MD ’43) who became a mentor. He was the pre-eminent hand surgeon in Toronto back then, and hand surgery always appealed to me as a sub-speciality. We did research projects together, I spent some elective time with him, and worked with him during my residency — I learned a lot from Jim.

How did you feel about pursuing a graduate research degree during residency?

During my residency, I decided to get more involved with the research side. I took an extra year and did basic science research, where I had an animal model and I did surgical research on flexor tendon healing — that’s where I received my Master’s degree. I think I was one of the first to have done that at U of T. Others had done research, but they hadn’t pursued the degree part of it and defended a thesis.

The advantage of this training was it fostered a more detailed appreciation for what research involves, the structure of a research study, the shortcomings, the advantages, how to facilitate a conclusion based on research. You really learn to be critical of scientific papers and articles, and you develop a more systemized approach to problem solving, which carries over into your clinical practice. It’s easier for patients to understand your treatment rationale when you can substantiate your conclusions.

You have established an endowed scholarship for surgeon-scientist trainees in the Division of Plastic Surgery — what inspired you to do this?

The idea of giving back. I’ve been doing this work for decades — and you think, ‘now what?’ Plastic surgery is something that defined most of my life and so it makes sense for me to do something that speaks to that. And let’s face it, economic realities on the academic side always exist — there are never enough resources, so I think if you have the opportunity to mitigate that a little bit, it’s fulfilling. It just kind of underscores the commitment I have to further plastic surgery research. At this point in my life and my career, it seems appropriate. I appreciate the work academics do, and I don’t want to lose that connection to the Department.

My scholarship helps to facilitate funding for those who are interested in research, and when an award is presented to a recipient, there is a connection between the person who receives it and person who donated it. You get to say, “Hi, I was in your place many years ago. I know how it feels.”

What advice would you have for current trainees pursuing plastic surgery?

You need to make sure what you end up doing is what you really like to do — don’t be pressured by circumstances or popular trends. The other thing is you shouldn’t narrow down your focus too early during training. You need to have a broad appreciation of the field of Plastic Surgery. If you don’t have a broad clinical exposure, your creativity is limited. From a practical point of view, more diverse training also gives you a greater range of job opportunities and more flexibility to choose where to locate your practice. Until you have some exposure to the broader range of what we do, it’s hard to decide what you might really like. Narrowing down is best left to later in your residency years.

Could you share some of the more memorable surgeries of your career?

I think the cases that are most memorable are those dealing with trauma. Trauma cases arise in an instant and your ability to assess the problem and devise a treatment plan must be done in the moment. It’s a challenging exercise. Specific injuries can be memorable — a dog bite to a child’s face, a worker who put his hand into a printing press — you can imagine. Thankfully, you don’t see these problems every day, but I think that being able to restore somebody who has had a traumatic injury and get them back as close as possible to how they were before is probably one of the most challenging and satisfying things that we do.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Revolutionizing Hospital Care with Artificial Intelligence: Dr. Muhammad Mamdani

“Everybody loves going to the hospital, right?”

Dr. Muhammad Mamdani jokingly posed this question at the annual Dean’s Lunch, an event hosted by Dean Trevor Young to thank and celebrate Faculty of Medicine donors.

Mamdani, who is a professor in the Faculty of Medicine, discussed how one of the biggest issues at a hospital are wait times. A patient going in with an intense headache will first wait to see a physician and then might have to wait to take a CT scan and then wait again for the results.

“It’s exhausting, simply waiting for diagnostic results, for example, could take up to six hours,” said Mamdani. “But, what if I told you we could reduce wait times for these results to minutes by using artificial intelligence?”

That’s exactly what Mamdani has set out to do as the founding director of the Li Ka Shing Centre for Health Care Analytics Research and Training (LKS-CHART).

According to Mamdani to make transformative changes in care, the first step is to break silos. He said, “U of T Medicine is a research powerhouse and has great partnerships with hospitals yet we find researchers, clinicians and scientists often work in silos.”

To change this, Mamdani has been collaborating with engineers, statisticians, clinicians, computer scientists and administrators at St. Michael’s Hospital to use innovations in data analytics to advance patient care. Six months ago, the team implemented deep-learning algorithms that make use of real-time data to predict patient volume, staffing requirements and determine each patient’s needs.

“It’s essentially a forecasting tool — think of how we use a mobile weather app to tell us if a snowstorm is coming tomorrow,” explained Mamdani “This system works similarly and can tell you on a Wednesday afternoon there will be 82 patients in the emergency room, nine who need mental health care and five who need intensive care. It has already helped us make better staffing decisions and has helped to ensure patients are receiving the appropriate care for their needs.”

And that’s just the start. Mamdani, who was recently named vice president of data science and advanced analytics at Unity Health Toronto — the first such leadership role in Canada — is also working on an artificial intelligence platform that can detect medical imaging abnormalities more accurately and efficiently, reducing image result wait times to less than five minutes.

“It really is amazing to see how far we have come not only in terms of developments in artificial intelligence and smart technology but their application,” said the Faculty of Medicine’s Executive Director of Advancement, Darina Landa. “There’s so much potential to make meaningful change in health and health care, and it is inspired and fueled by the generous and visionary support of our donors.”

Dean Young agreed saying, “It is through the collective impact of students, educators, researchers and donor support that we have reached new heights, including ranking sixth in the world for our clinical, preclinical and health programs by Times Higher Education.”

U of T’s Chancellor Rose Patten spoke about her own very personal connection to the Faculty of Medicine and her support of scholarships and student awards. She said, “This is one of the world’s top faculties of medicine — a place that is forging new paths in care and treatment and pushing the boundaries of discovery. Together we are keeping it at the top."

Mamdani encourages the U of T Medicine community to continue to push further with collaboration among different departments and faculties. Mamdani explained, “One of the worst things you can do is ask a clinician to build a data network or ask a computer scientist to solve a clinical care issue — but, by bringing their expertise together they can drive change where we are no longer waiting for the future, we are creating it.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Rohini Chopra

Coming to the Table for Cancer Research

The annual Hold ‘em for Life Charity Challenge brings business leaders together to raise vital funds for cancer research at the University of Toronto and its affiliated hospitals.

The annual Hold ‘em for Life Charity Challenge brings business leaders together to raise vital funds for cancer research at the University of Toronto and its affiliated hospitals.

When his sister Katie was first diagnosed with breast cancer, real estate developer Andrew Hoffman took it as a call to action. Hoffman, the CEO of CentreCourt Developments, partnered with Tony Reale, a managing director at BMO Capital Markets, to launch an event aimed at raising funds for cancer research.

Together, they created the Hold’em for Life Charity Challenge, a platform for industry leaders to come together for a gala evening in support of cancer research. The title of the charity reflects the event theme: Texas Hold’em poker, played in an authentic Monte Carlo-style atmosphere. There are two events each year, one for real estate industry professionals and one for those in the asset management sector.

More than $33 million raised in just over a decade

Since its creation in 2007, Hold‘em for Life has donated more than $33 million to cancer research across the GTA, supporting new discoveries in genetics, molecular medicine and breast cancer risk factors, and have increased the University’s capacity to train young researchers. Highlights include a chair in prostate cancer research, life-saving breast and prostate cancer treatments, and a PhD fellowship program.

Supporting oncology clinician-scientists

This year, Hold’em for Life made a transformative $16.4 million commitment to the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine and partner hospitals, and established the Hold’em for Life Oncology Fellowship Program. Worth $50,000 per year, the Hold‘em For Life Fellowships are open to U of T clinical residents and fellows who are also pursuing cancer research at any of U of T’s nine fully affiliated teaching hospitals.

“When you’re building a business, it all comes down to having great and dedicated people. In exploring how we wanted to earmark our future donations, we were excited by the opportunity to invest in the young medical talent dedicating their lives to cancer research and clinical work. Developing the fellowship program was a perfect fit,” says Hoffman. “Our gift reflects how industry can come together and make a difference. And having the program under the umbrella of U of T’s Faculty of Medicine is something we all feel good about.”

Investment in U of T and Partner Hospitals

“We are incredibly grateful for Hold‘em For Life and its volunteers for making this transformative commitment to the next generation of oncology clinician-scientists,” says Trevor Young, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. “The gift will allow young scientists to unlock the potential of new diagnostics and therapeutics and improve personal care. It’s also a major investment in the research and clinical medicine powerhouse formed by U of T and its hospital partners.”

In total, 46 Hold’em Fellowships have already been awarded. Recipients hail from Canada, Finland, Ireland and Brazil, meaning talent will both stay in Canada and go back to other countries, creating a ripple effect of shareable, global knowledge.

“We are so pleased to be a partner in this incredible initiative to invest in the young trainees who are advancing our understanding and treatment of various cancers,” says Michael Burns, President & CEO of the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. “This tremendous gift to our hospitals will have lasting impact here in Toronto, across Canada and globally.”

Louis de Melo, CEO of Sinai Health Foundation says, “In a short time, Hold’em for Life has built tremendous capacity for cancer research across Toronto-area hospitals. We’re so very fortunate to once again be a beneficiary of the charity’s efforts to support the very best clinician-scientists in Toronto.”

For Hoffman, he looks forward to increasing the fundraising efforts and the amount of funds available to the fellowship program and is exploring other industry sectors that wish to embrace the Hold’em for Life model. “Volunteers with a shared passion can make great things happen,” he says. “We’re so pleased with the impact our charity has had on causes that are important to us, and we are grateful to U of T and the hospitals for working with us to design a program that will ultimately benefit clinician-scientists and cancer patients here in Canada and around the world.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Anjali Baichwal

UofTMed Alum: Changing Lives with Assistive Technology

I’ll never forget working with a client who had Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia in 1999. He was a resident at a long-term care home and used a powered wheelchair to get around the residence.

Because of his poor motor function and delayed response time he had trouble using his wheelchair and would bump into staff members. It was clear, in no time he would be bumping into other residents, potentially causing them to have a terrible fall. We tried many strategies with him to minimize the risks but ultimately, we had to take his wheelchair away.

My client was devastated. The wheelchair was the only way he could get around on his own. And as an occupational therapist, it is my job to help clients perform everyday activities independently and comfortably.

I was faced with scenarios like this often. I constantly found myself trying to balance a client’s need for and right to independence, and someone else’s need for safety.

In this situation, the wheelchair was no longer an option. But, I knew there had to be other solutions. So, I went back to university to research and develop new technologies that can empower seniors and people with disabilities.

I enrolled in U of T’s Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, in a collaborative program with the Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. I worked in Professor Geoff Fernie’s lab, where we produced and evaluated adaptations to powered wheelchairs.

Our team created sensors to detect obstacles and prevent collisions and developed new steering interfaces to help people with cognitive impairments navigate their environments more easily.

In my postdoctoral research with Professor Alex Mihailidis, we worked on innovations in robotics and artificial intelligence. For example, we tested a robot intended to help remind seniors with Alzheimer’s disease of the steps needed to complete tasks like making a cup of tea or washing their hands. It was an exciting time to be part of rehabilitation sciences.

At the same time, I was aware that even with all of these opportunities in the pipeline, not all of my clients would be able to access them. Robots, artificial intelligence and smart home technology are expensive and public health care funding does not cover the costs.

My fear was rather than helping seniors and people with disabilities by creating technological advancements, I was just deepening the divide between those who can and cannot access health and social care supports.

So, when the opportunity came up to investigate the ethical issues around equity of access to assistive technology, I jumped at it.

I am currently co-leading a national research initiative with Professor Mike Wilson at the McMaster Health Forum funded by AGE-WELL NCE and partnered with March of Dimes Canada. We are working to improve equitable access to assistive technology in Canada by working with seniors, people with disabilities, caregivers, policymakers and health care providers to understand the unique challenges they face.

Now, we are conducting a national survey and holding a symposium to understand Canada’s priorities around this issue. We hope the findings from these initiatives will help us redefine our approach to programs and services for assistive technology in health and social care — making it more accessible to those who need it, regardless of financial circumstances.

With the ageing population in Canada increasing and a larger number of people living with chronic conditions and disability, technology has a big role to play to improve quality of life. Equitable access to assistive technology is a critical piece to people gaining control over their lives and protecting their rights to express themselves and be heard and included in society.

Dr. Rosalie Wang, PhD ’11, is an occupational therapist and Assistant Professor at U of T’s Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy. As an AGE-WELL investigator, she also leads a national project on enhancing equitable access to assistive technology. Join the conversation by writing us your thoughts on power in medicine, or by attending our UofTMed Inside the Issue panel discussion on December 4th.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Dr. Rosalie Wang

Lifetime Achievement Award – Global Impact

Lifetime Achievement Award – Global Impact Lifetime Achievement Award - National/Community Impact

Lifetime Achievement Award - National/Community Impact Humanitarian Award

Humanitarian Award Emerging Leader Award

Emerging Leader Award MD 25th Anniversary Award

MD 25th Anniversary Award