Faces of U of T Medicine: Natalie Landon-Brace

When it comes to drug discovery research, there can often be bumps in the road, including promising lab results that don’t translate into safe treatments for people. Natalie Landon-Brace is in her first year of the MD/PhD program and hopes to take this challenge on during her doctoral studies. A recipient of the 2017 Dean Catharine Whiteside Scholarship for Clinician-Scientists, Landon-Brace hopes to explore platform technology — using or adapting a relatively simple system and applying it in different contexts — to tackle such problems. Recently, she spoke with writer Erin Howe about her experience so far in medical school and her research plans.

What did you do before you began medical school?

My background is in biomedical engineering — I did my undergraduate studies here at U of T in engineering science. I’ve done a bit of work in cancer genetics and bioinformatics. I’ve also done a bit of work in platform technologies. One of my projects involved a cell-based drug delivery system for prostate cancer.

During your undergraduate studies, you spent a year in Boston as part of the Professional Experience Year Program. What was that experience like?

I went to Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and worked on a cell-based drug delivery project. It’s very different from here. I’m from Toronto originally, and so it was nice to get a different perspective and spend some time living in a different city. It was exciting to be in that fast paced, innovative environment. There are a lot of people doing very cutting edge, high-risk, high-reward projects, so it was cool to be immersed in that.

Tell me more about the research you were doing while you were there.

I was sort of a jack-of-all-trades sort of intern. The main project I worked on involved cancer drugs. New drugs are being developed and although they might work well in a dish or even in an animal model, some can’t be used in people because the therapeutic window is too narrow. That means there isn’t much difference between the dose at which the drug is effective and the dose at which it is toxic.

I was in Jeff Karp’s engineering lab, which researches biomaterials, stem cell technology and platform technology. In collaboration with a clinician-scientist, we wanted to develop a system that would let us more specifically deliver drugs to tumour sites to use these new drugs without the significant toxic effects.

My project involved the innate immune system and white blood cells. Our collaborators had demonstrated that some drugs can increase white blood cell infiltration to tumours. We wanted to see if we could harness that effect and use white blood cells as carriers to deliver drugs for us.

Why did you choose to take part in the MD/PhD Program? What made this an appealing option?

I always knew I wanted to consider doing an MD and a PhD in the future and they were always together in my mind. I really want my future career to involve patient care, but also the opportunity to innovate and try to improve health care through new discovery. My experience in Boston cemented this for me and made me confident that the MD/PhD program would be the right fit. I think it was important to branch out and see what the academic environment is like elsewhere, but I was easily lured back to Toronto. I think some of the best medical innovation and research in the world is happening here and that sealed the decision to stay.

You’re the recipient of the 2017 Dean Catharine Whiteside Scholarship for Clinician-Scientists. What was your reaction to learning you’d received this honour?

I met so many impressive people on the interview trail, I think the MD/PhD applicant pool is incredibly qualified. I was amazed that they picked me. It’s an incredible honour to be selected and ultimately, played a big part in my decision to stay at U of T.

You’re planning to begin your PhD in September of 2018. What do you hope to focus on?

I’m interested in developing platform technology to improve our understanding of disease and to increase the clinical relevance of laboratory discoveries. An example would be looking at how to grow 3D tissue models in the lab with real patient cells. Ultimately, the hope is to use these types of model systems to improve and expand treatment options for patients. This could take the shape of discovering new potential drug targets or improving our ability to determine which drugs might work best on which patients. The possibilities are extremely broad.

What’s your favourite thing about the MD program so far?

The main thing is that everything feels relevant. It’s easy to see how what we’re doing in in the Foundations Curriculum is relevant to the future — especially the clinical skills and case based learning. There’s also a lot of opportunity to learn how to interpret things within the context of clinical problems and scenarios. It’s possible to see the progression from knowing very little to where we hope we’ll end up one day.

What do you enjoy doing when you’re not studying?

I teach swimming lessons and do a lot of tutoring. I enjoy working with kids. It can be challenging, but fun and very rewarding as well. I also love to play tennis. Sports are definitely my big outlet — and Netflix.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

University of Toronto Science Rockets Into Space

A University of Toronto scientist will perform real-time blood cell analysis on astronauts to determine how time, space and speed affect the immune system – novel research he hopes will lead to new understanding of how stress and other environmental factors impact our ability to fight disease.

Dr. Chen Wang, professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and a clinician-scientist at Mount Sinai Hospital, will lead the project, called Immuno Profile, to study the astronauts on the International Space Station over the next five years. Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques, a physician, will be part of the next mission to the Space Station, and will participate in a number of Canadian-made health experiments announced by the Canadian Space Agency.

“It has been documented that spaceflight has significant impacts on the immune system, probably due to microgravity, high G force and stress,” says Wang. “So far, all the tests have been performed on ground with blood samples taken before and after spaceflight. This study will be the first time we’ll be able to see the immunity changes in real-time on the International Space Station.”

Wang will use a novel device that astronauts can operate to take finger-prick blood samples on themselves during their flight missions. They will then beam the results down to him for analysis.

“We expect to see immune cell and cytokine mediator changes,” says Wang. “We’ll develop a way to identify different types of immune cells and to see if the cells are functioning well or not.”

Immune dysfunction relates to many diseases, including cancers, viral infections, MS, type I diabetes, and even the aging process, he says. A space flight provides a unique environment in which to study immune system stressors: the weightlessness of space can also be used to learn more about the less-understood lymphatic system, which depends on pressure to flow properly.

“We know that lymphocytes are major components of the immune system, and many cytokine immune mediators regulate the immune system in response to stress and environments,” says Wang. “We hope to develop a new model for how the immune system responds to circadian rhythm, and various stresses.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Heidi Singer

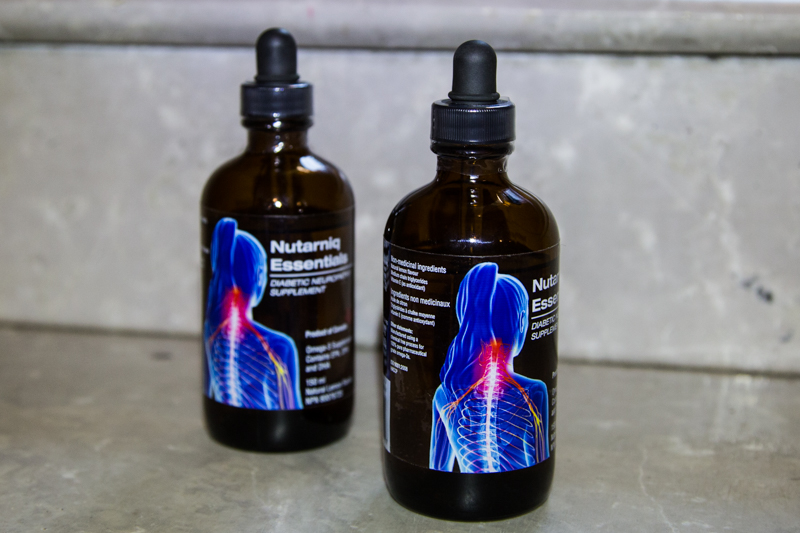

H2i Spotlight: Nutarniq

Nearly 11 million people in Canada have diabetes or pre-diabetes, and it’s estimated about half will develop a form of nerve damage known as diabetic neuropathy. Caused by high blood glucose levels over an extended period of time, this long-term diabetes complication can affect nerves in the arms, hands, legs and feet and lead to a loss of sensation or feelings of burning, tingling or sharp pain. But research by Evan Lewis (PhD Nutritional Sciences, ’16) shows such damage can be reversed. Lewis recently spoke with writer Erin Howe about his non-drug nutrition therapy, Nutarniq Essentials.

Nearly 11 million people in Canada have diabetes or pre-diabetes, and it’s estimated about half will develop a form of nerve damage known as diabetic neuropathy. Caused by high blood glucose levels over an extended period of time, this long-term diabetes complication can affect nerves in the arms, hands, legs and feet and lead to a loss of sensation or feelings of burning, tingling or sharp pain. But research by Evan Lewis (PhD Nutritional Sciences, ’16) shows such damage can be reversed. Lewis recently spoke with writer Erin Howe about his non-drug nutrition therapy, Nutarniq Essentials.

How did you arrive at this concept? What inspired you?

I was an athlete on the Canadian sailing team for a number of years and the idea of looking into the impact of nutrition and performance interested me. Most supplements focus on trying to make muscles bigger or burn energy better. But for our muscles to function, we need our nerves to carry signals from our to brains to say, ‘run harder, go faster, jump higher’.

When I started my PhD, there was nothing available for athletes to improve nerve function. I investigated the use of omega-3s to improve nerve-muscle interaction. Following the successful outcome of my research, I decided to move away from sports performance and work to help people who might need help getting up the stairs or walking around the block because of their nerves and muscles weren’t working optimally. The largest group that needed help was people with diabetic neuropathy. If we can use nutrition to help people improve their nerve-muscle function, that would be a huge win clinically and for the healthcare system.

What’s the status of Nutarniq right now?

We founded our company at the end of 2016 and launched our first product, Nutarniq Essentials Diabetic Neuropathy Supplement, in June. That coincided with the publication of our diabetes trial in Neurology. It was really important for our company to launch with the publication because we’re not just another supplement company. We’re a research-based company.

We founded our company at the end of 2016 and launched our first product, Nutarniq Essentials Diabetic Neuropathy Supplement, in June. That coincided with the publication of our diabetes trial in Neurology. It was really important for our company to launch with the publication because we’re not just another supplement company. We’re a research-based company.

Your product is a nutritional supplement, but you mentioned it could be reclassified as a medication.

We’ve been in discussions with Health Canada. If a nutrient or supplement can improve health outcomes in chronic diseases — diabetes, cancer, anything of that classification — they could consider that a drug, so it’s something we’re exploring. Right now, our Nutarniq Essentials is classified as a natural health product.

So, your product is already on the market, then.

We sell Nutarniq Essentials online in Canada and through a growing network of retail partners. We’re also expanding throughout Canada with distribution to allied health care professionals who work with and support people with diabetes.

What makes you passionate about this?

If we can use targeted nutrition therapy instead of drugs, then we can lower risk of side effects from therapy. And if we can use nutrition preventatively or restoratively, we could hopefully reduce the burden on our health care system and in painful conditions, then we can reduce the use of pain medications.

How does the product work?

The product is a pharmaceutical grade Omega-3s from seal oil, which has a different chemical structure compared to fish oil Omega-3s. Seal oil can be absorbed at two sites — one in the mouth and one in the general digestive tract. This leads to higher bio-availability, which means that the body can absorb and use the nutrients more effectively. Our general diet doesn’t provide enough of the essential Omega-3s we need so, when given in appropriate doses for the proper duration, then our clinical trials showed we were able to regenerate nerves.

How does your product differ from fish oil or other Omega-3 products?

Most people are familiar with the Omega-3s come from seeds and nuts. That type of Omega-3 is made up of very short chains our bodies can’t use for nerves. Fish oil has longer chain Omega-3s, like EPA and DHA. Seal oil contains them, too, but it also has DPA, another Omega-3 that resolves inflammation and helps nerves restore themselves. So, we have three Omega-3s in a different concentration than fish oil and two different routes of digestion and these things together provide a more powerful effect for people.

Who has helped to mentor or inspire you at U of T?

During my PhD, my primary supervisor, Tom Wolever, a professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, was a great inspiration because he’d also developed some commercialized some of his work. He was also a great mentor in terms of research design. I also worked with Greg Wells, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, who helped with the sports performance side of things and was also very keen on commercializing of research. I was also fortunate to develop relationships with clinical partners like, Vera Bril, Head of the Division of Neurology and Director of Neurology at University Health Network, and Bruce Perkins, a professor in the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism. I was able to bring a group of experts together to support my development in sports performance research and diabetes research and draw on all of their expertise to get to where I am now — commercializing great research, running a company and continuing our clinical research, which is exactly where I want to be.

What’s next for Nutarniq?

Right now, we’re in the final stages of developing our proprietary product for our next clinical trial. We’re also expanding our distribution along with sales and marketing. I’m learning a lot of fun things on the fly. So far, we’ve had great response and the company is growing every day.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Canadian Researchers Lead International Effort to Prevent Chronic Disease

University of Toronto researchers will lead the Canadian arm of a $40 million research project to advance child and family health worldwide.

The Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative (HeLTI) seeks to prevent chronic disease in Canada, China, India and South Africa. Parliamentary Secretary Bill Blair announced the new funding at St. Michael’s Hospital on Nov. 20.

Cindy-Lee Dennis, a professor in the Faculty of Nursing and Department of Psychiatry, will lead the Canadian arm of the study, which will receive $17-million from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The Canadian-focused study will work with 10,000 potential parents to improve health and habits even before pregnancy.

“One-third of Canadian children are overweight at age 5,” says Dennis, who is also Women’s Health Research Chair at St. Michael’s Hospital. “HeLTI seeks to prevent chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease by understanding the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to these diseases and then studying interventions designed to promote good health from pre-conception to early childhood.”

Two other Faculty of Medicine scientists will lead an arm of the study. The South Africa arm will be co-led by Stephen Lye, a professor in departments of Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynaecology the Senior Investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (LTRI) of Sinai Health System and Executive Director of the Alliance for Human Development at LTRI. The India arm will be co-led by Stephen Matthews, professor of Physiology, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Medicine at U of T and Director of Research at the Alliance of Human Development, LTRI.

CIHR has also recently launched a process to create an Indigenous component of HeLTI in Canada in consultation with Indigenous communities.

The Canadian HeLTI arm will address healthy habits and practices in four phases—pre-conception, pregnancy, infancy and early childhood. In each phase, participants will receive:

• telephone-based collaborative care provided by nurses

• personalized e-health interventions, based on identified risk factors that target health behaviours related to nutrition and breastfeeding, physical activity and sleep

• information on a supportive and nurturing environment for the children and their family

“This research initiative will guide the development of new approaches to preventing chronic diseases and lay the groundwork for a healthy and productive future for our children,” says Canada’s Minisiter of Health, the Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor.

In total, Canada’s investment in HeLTI is $33.4 million over five years. An additional $7.8 million is being provided through a partnership with national research agencies in India, China and South Africa.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Faces of U of T Medicine: Tahani Baakdhah

Known to her 11,000 Twitter followers and 2,225 Instagram followers as @thepurplelilac, Tahani Baakdhah is passionate about sharing her love of science with the public. Baakdhah is a PhD student studying stem cells in the retina at the Institute of Medical Science. She’s also an avid crocheter who uses her artistic talents to bring the neurons, photoreceptors and cells she studies to life. She recently spoke with writer Erin Howe about her research and her unique way of sharing her work and promoting science literacy.

What inspired you to crochet your PhD?

Every time I look under the microscope, I see different kinds of cells, which motivates me to create my own patterns to crochet. I took up the craft in 2010, after I joined Instagram, which was a new platform back then. I saw posts about amigurumi, which are little crocheted figures. My kids were still little and I wanted to make custom toys for them. I watched a lot of YouTube videos, practiced all kinds of stitches and taught myself how to crochet. By the end of 2012, I joined the Toronto Etsy team and started to participate in their mobile pop-up markets. I started to make science crochet in June, when SciCommTO invited me to help them introduce the Knit a Neuron workshop in Toronto, an event that originated in the UK.

Tell me about your research.

I’m a member of Professor Derek van der Kooy’s lab. We’re trying to grow retinal stem cells from adult mouse models or pluripotent stem cells, which are like master cells with the potential to make any kind of tissue or cell. We’re also trying to differentiate these kinds of stem cells to various kinds of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which is the pigmented layer of the retina. As well, we’re trying to inject these cells into blind mice to see if they will work, integrate and interact within the blind model.

For my thesis, I’m working on expanding the number stem cells of in a bioreactor. These kinds of stem cells are very rare — only one in 1:500 cells in our eyes are stem cells. These cells are multi-potent, they can give rise to a variety of different kinds of retinal cells in a dish. So, if we want more photoreceptors and more of the pigmented layer, then we need to encourage the stem cells to divide symmetrically to create more versions of themselves. In another project, I’m trying to convince stem cells to produce more of the RPE layer. It’s a challenge and many labs around the world are having a hard time doing this.

You’ve also been part of other initiatives to promote science communication. Can you tell me about some of these activities?

I’ve been fortunate to do some science outreach with the Donnelly Centre. In September, I also participated in Soapbox Science Toronto and got to meet a lot of parents and kids. I used my crocheted models to explain to the children how we see the world, what blindness is and how we can treat it with stem cells. I’ve also been invited to many symposiums, conferences and talks just to speak about my science art. People often ask me afterward for the patterns I’ve created, which led me to write a science crochet book. The manuscript is finished and I’m now looking for a publisher. It’s a mix of crochet patterns, science communication and education.

What makes you so excited about science communication?

The public is so far removed from scientific information. There are scientific papers, which aren’t really open access. Or there’s traditional media, but most journalists aren’t scientists. And there aren’t many ophthalmologists or researchers who use social media. They’re busy and they might go to conferences or symposiums, but they’re talking to other scientists. It’s nice to go to people where they are and reach them on whatever platform they use.

You’re planning to complete your PhD next year. What are you hoping to do next?

I’d like to finish my PhD and follow it up with a two-year post-doctorate to build more experience. I completed medical school in 2003 at King Abdul Aziz University Faculty of Medicine and I would love to further my clinical training to become an ophthalmologist. This is my dream.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Better Medicine Through a Better Understanding

Getting Ry Moran on the phone is no easy task. The Founding Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation is in high demand. When I do reach him, it’s the day after the 3rd Annual Building Reconciliation Forum concluded at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. The forum was titled The Journey Toward a Reconciled Education System and brought together leaders from universities, colleges and Indigenous communities to take action on reconciliation, creating meaningful and lasting institutional change.

“It’s been a busy week,” Moran said in an understated tone. “But it’s been very good. We had a lot of a very difficult conversations. But, my job is to encourage difficult conversations.”

Moran will engage the University of Toronto community in some of those challenging discussions on Thursday November 23 when he delivers the 2017 Dr. Marguerite (Peggy) Hill Lecture on Indigenous Health.

In Moran’s talk, entitled Towards A Trauma Informed Understanding Of Reconciliation, he will press the medical profession to recognize its special responsibility to address Indigenous health. This first requires an understanding of the trauma suffered by Indigenous communities in Canada over centuries to understand the underlying causes that can present as different health issues, including mental, physical and spiritual.

“We have a sickness in this county that is born from the experience of colonialization. And it can manifest itself in many different forms. I think medical professionals, who want to be healers, will want to understand the underlying causes of this illness, and not just treat the symptoms,” Moran said.

Among the challenges are higher rates of diabetes, hypertension and heart illness as well as high rates of smoking, alcohol consumption and drug abuse.

“Why are they smoking or drinking more? It’s not because they don’t care about their health. We have heard from survivors that they are using cigarettes as a coping mechanism to deal with stress, or drugs and alcohol as numbing agents to deal with the pain. They are self-medicating,” he says.

Critical to moving forward, Moran believes, is hearing from both survivors and elders.

“They are two sides of the same coin; they represent both truth and reconciliation,” said Moran. “That means listening to the trauma perpetrated on Indigenous peoples, and that is very hard to hear. But we need to sit in our discomfort. But at the same time, we need to hear from our elders, because the state of Indigenous communities now is not what it has always been. There is a millennium of history when Indigenous communities had some of the best health outcomes in the world. We need to de-normalize the current state of Indigenous health and return to the state where we are in balance with the earth.”

Moran is a proud member of the Métis Nation of Manitoba. As the first Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), he’s helping guide the creation of an enduring national treasure — a dynamic Indigenous archive built on integrity, trust and dignity. He came to the Centre directly from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). On the TRC’s behalf, he helped gather nearly 7,000 video/audio-recorded statements of former residential school students and others affected by the residential school system. He was also responsible for gathering the documentary history of the residential school system from more than 20 government departments and nearly 100 church archives – millions of records in all.

“Ry’s experience with the TRC process, and now in his role as the Director of National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, provides him with a unique perspective to identify the trauma that Indigenous Canadians have faced, but also to help us see opportunities for reconciliation,” said Dr. Jason Pennington who, with Dr. Lisa Richardson, serves as co-lead of Indigenous Health Education in the MD Program. “As medical professionals, we must heed the calls of the TRC recommendations and commit ourselves to forging improved relationships with the Indigenous communities we serve,” added Richardson.

The U of T Medical Alumni Association, in partnership with the Faculty of Medicine’s Office of Indigenous Medical Education, will host this lecture from 5 to 6 pm at the Campbell Conference Facility at the Munk School of Global Affairs. The event is now full, but it will be webcast online beginning at 5 pm on November 23.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Liam Mitchell

No Longer Faceless

Documentary produced by U of T professor targets stigma by bringing audience into mental health ward

The stigma surrounding mental health can be almost as harmful as the illness itself. As part of the effort to end that stigma, Dr. Anna Skorzewska produced a documentary that invites the audience into the Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at University Health Network. Directed by Jason Lapeyre, Faceless is an interesting and intimate portrait of an inpatient unit in the cinema verite style. It was an official selection of the Big Sky Film Documentary Film Festival. Skorzewska, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Director of the PICU, spoke with the Faculty of Medicine’s Liam Mitchell about the documentary and how it reveals the faces of a group often considered faceless.

What motivated you to produce this documentary?

I had already started a film program in collaboration with the Toronto International Film Festival for psychiatric inpatients which consisted in showing films to patients, inviting people involved in film to present and discuss films and provide filmcraft workshops. We thought it would be important to document the program and applied for a grant to make a film about it. When we got the grant and started working on it, it evolved into a film about the inpatient ward.

Documentaries allow people to tell their stories, but it can also expose their vulnerabilities. How did you work with patients to ensure they felt secure in telling their stories?

We went through a lengthy and arduous process with the hospital to ensure that patient's confidentiality and rights were respected. The patients had complete control over their involvement. They could pull out at any time. Also, the patients were the only ones who vetted the final edit of the film. We were prepared to take out anything they didn't like. Fortunately, they all loved it.

It is interesting though that, for a film that was in part made to fight stigma and as an advocacy tool, most of the patients did not want their faces to be seen. They were worried that they would be recognized in the community and that it would affect their ability to get a job so we couldn't put many faces in the film. As a result, we called the film Faceless.

How did the documentary help you reflect, as a psychiatrist, on the care patients received and the environment in which it was delivered?

We tried to portray the ward in as honest a way as possible. That's partly why we did it in a cinema verite style. It was difficult at times because the portrayal of the unit was sometimes unflattering and some of the information conveyed was false. This was both because patients don't always know what is happening behind the scenes or why they happen the way they do and because the descriptions represented perceptions which are sometimes distorted. I had to stop myself from correcting or explaining some of the information in the film. On the whole, it was a wonderful experience for the whole unit. The director was gentle and non-judgmental. (In fact, he told me that within a week on the ward all of his preconceptions about inpatient psychiatry were completely eliminated.) He spent time with all the staff and patients. I believe the nurses learnt something about the patients and patients learned things about the nurses. There was a dialogue happening.

This isn’t your first encounter with films. You previously partnered with the Toronto International Film Festival to establish Reel Comfort. How do films advance understanding and teaching about mental illness?

Reel Comfort was the result of a chance meeting with Jane Schoettle, a long-time TIFF programmer and founder of the TIFF kids film festival, a remarkable woman with enormous vision and creativity. From that meeting, however, a conversation began. The result was Reel Comfort, for which we got a Johnson and Johnson funded grant from the Society of the Arts in Medicine, one of only six given and the only one in Canada. The point was to provide a hospital activity that would be stimulating and entertaining in a universal medium that appeals to everyone. I also wanted our patients to feel that they were important enough that an international and prestigious arts festival would take an interest in them and that famous directors, editors, actors and others would be interested in talking to them.

Our program has now expanded to most of the teaching hospitals and some others. TIFF has a wonderful full-time coordinator for the program, Elysse Leonard, who has grown the program and added elements.

Do you see other opportunities for the medical profession to use documentaries or movies to advance public perceptions or support teaching?

I believe that all the arts, humanities and social sciences have a significant contribution to make to public perceptions of medicine in general. I also believe it can help teach things that are difficult to teach – collaboration, communication, empathy, professionalism, and critical thinking. I have developed a seminar for psychiatric residents on the arts in psychiatry in which I use literature, film, theatre, visual art and philosophy/sociology/anthropology/history to teach various aspects of psychiatry. This includes placing some of our practices into historical perspective (humbling), to a critical examination of psychiatric nosology (also humbling), to helping residents make the imaginative leap into other people’s lives. I’ve also just co-edited a book, with Allan Peterkin, on the use of arts and humanities in postgraduate medical education that will be published by Oxford University Press in the spring so stay tuned.

Faceless is available to rent or buy on Vimeo. Twenty per cent of the profits from the documentary will be donated to the inpatient psychiatry unit at Toronto General Hospital.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Liam Mitchell

Faces of U of T Medicine: Kirill Zaslavsky

As an MD/PhD student, Kirill Zaslavsky’s educational experiences have ranged from applying CRISPR to human stem cells to study neuropsychiatric disease to clerkship. Earlier this year, Zaslavsky completed his PhD, which focused on the molecular and neurophysiological causes of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). He’s now in the third year of MD studies. Zaslavsky has also become a voice for others working to become ‘double doctors’ in his role as President of the Clinician Investigator Trainee Association of Canada (CITAC,). Zaslavsky spoke with writer Erin Howe about his research and the importance of being an advocate for basic science.

Congratulations on completing your PhD earlier this year! Tell me about your research.

I studied ASD in the Ellis Lab at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects more than one per cent of children, predominantly boys. It affects the way a person communicates with others and how they relate to the world around them.

Recent advances in genetics have revealed a complex picture, with associated mutations in over 100 different genes. Roughly half of those genes govern the function of synapses — the chemical connections necessary for communication between neurons. While this suggests ASD is a disorder of brain wiring, understanding the functional consequences of these mutations is a challenge because there’s a lack of available neuronal tissue from living individuals with ASD.

To address this knowledge gap, the Ellis Lab generates induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) from people with ASD and converts them into live neurons. This recently-developed approach allows generation of an inexhaustible supply of neurons for functional and mechanistic studies. Using CRIPSR-Cas9 genome engineering, I showed that neurons with mutations in a particular ASD-associated gene become larger, develop more complex morphology and make more synapses. Together with our collaborators in the Salter lab, we then showed these changes are associated with a several-fold increase in the activity of excitatory synapses, which increases the likelihood of neuronal activation. These results are consistent with the little we know from post-mortem studies of brains from people with ASD, which generally show an increase in synapse density.

My hope is that as more ASD genes are explored in this way, we will approach a molecular understanding of ASD that will help inform development of therapy.

What appealed to you about the MD/PhD program?

Early influences and mentors played a significant role in my decision to pursue both degrees. When I was an undergraduate student in neuroscience, Professor Andrew Baines, himself a former clinician-scientist, was highly supportive of a career in both medicine and science. Through one of the assignments in his course, I connected with Paul Frankland, an associate professor in the Department of Physiology studying the organization of memory and hippocampal neurogenesis at SickKids. When I was a member of the Frankland lab, I worked with Scellig Stone, a neurosurgery resident completing his PhD. Stone — who is now a professor at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Movement Disorders and Deep Brain Stimulation Program at Boston Children’s Hospital — showed me how clinical practice and research are linked.

After these experiences, the MD/PhD program at U of T was a logical choice after this. The scientific community at the university is vibrant and collaborative. The ability to do my PhD early on in my training gave me the opportunity to do fundamental research with people who are leaders in their respective fields.

As a student who has just returned to MD studies, how would you describe the ways how your studies and PhD studies complement one another?

While the PhD was a period of highly-focused, narrow study, my experience in the MD has so far been broad and all-encompassing. The PhD was much more about learning how to think critically, approach difficult problems with creative solutions and persevere in the face of difficulty. Going through the MD curriculum, I find myself more critical of the evidence on which medical knowledge is based. Doing my PhD as human genome sequencing became increasingly accessible and genome editing ceased to be science fiction changed how I view the future of medicine. There is a lot of exciting work to be done.

You’re also involved with CITAC. What kinds of things have you been working toward as the organization’s president?

The primary goal this year was to advocate for support for clinician-scientist training.

CIHR terminated MD/PhD program support in 2015 and since then, we’ve contributed to a body of work evaluating the performance of these programs in Canada. For example, a national survey of MD/PhD alumni conducted out of UBC showed these programs are successful in generating academic physicians and most graduates work as clinician-investigators. So, we find it perplexing that there’s no federal support for this training pathway.

We also found this issue is part of a broader, more pervasive theme in Canadian research. The Naylor Report, a review of Canada’s Fundamental Science Review published earlier this year, makes it clear our research ecosystem has become underfunded and disorganized. Canada is the only G7 country to decrease spending on research as a percentage of GDP in the last 15 years. We’re also spending a jaw-dropping 32% less than the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) average.

As prospective clinician-scientists, our future is inextricably linked to the health and success of the broader research community and why we hope the recommendations in the Naylor Report are implemented in full.

What do you enjoy doing when in your spare time?

Catching up on sleep, spending time with those closest to me, and enjoying a good show (everyone needs to see Planet Earth II).

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

U of T Graduates Build Convertible Surgical Tool

Around the world, 15 million laparoscopic operations are performed each year. Also known as ‘keyhole’ surgeries, these procedures help reduce infection risk, blood loss and recovery time. But, in some of these minimally invasive surgeries, doctors need to remove the device used to create a tunnel into the patient’s abdomen — called a “trocar” — to replace it with a larger one in order to use bigger tools. Three recent U of T graduates launched a start-up called Xpan to solve this problem. Zaid Atto, Seray Cicek and Chevis Dilbert created a trocar that allows laparoscopic tools to be used interchangeably. The team recently won one of three Student Innovation Fellowship prizes through the H2i Pitch Perfect Competition. Faculty of Medicine writer Erin Howe spoke with Atto and Cicek about their invention.

Around the world, 15 million laparoscopic operations are performed each year. Also known as ‘keyhole’ surgeries, these procedures help reduce infection risk, blood loss and recovery time. But, in some of these minimally invasive surgeries, doctors need to remove the device used to create a tunnel into the patient’s abdomen — called a “trocar” — to replace it with a larger one in order to use bigger tools. Three recent U of T graduates launched a start-up called Xpan to solve this problem. Zaid Atto, Seray Cicek and Chevis Dilbert created a trocar that allows laparoscopic tools to be used interchangeably. The team recently won one of three Student Innovation Fellowship prizes through the H2i Pitch Perfect Competition. Faculty of Medicine writer Erin Howe spoke with Atto and Cicek about their invention.

What inspired your expandable laparoscopic surgery tool?

Atto: We’re recent Biomedical Engineering graduates from the Department of Engineering Science. Through our final year capstone project, we learned how surgeons sometimes need to remove a trocar during a procedure to replace it with a larger one to use larger tools. Because the trocar is like a tunnel that other equipment needs to fit through — sometimes more room is required mid-procedure. Priscilla Chiu, an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery and staff surgeon in general and thoracic surgery at The Hospital for Sick Children had brought this problem to one of our instructors. We thought, what if there was a way to allow larger instruments to be used without having to remove and replace trocars?

Cicek: Both of our fathers have had laparoscopic surgeries. There were complications during my dad’s operation and instead of being in the hospital for one day, he had to stay for three. We don’t know if our trocar might have helped prevent the complications my dad experienced, but there will be cases when it could save people days in hospital. Knowing we can make a change motivates us.

How will Xpan improve surgical outcome?

Cicek: Replacing a trocar mid-surgery has the potential to expose patients to more risk. It also adds time and expense to the procedure. Our device will prevent these problems.

Atto: In addition, our tool gives surgeons flexibility and convenience they didn’t have before.

Who has mentored or inspired you here at U of T?

Atto: Dr. Chiu is our clinical advisor and continues to inspire us. Chris Bouwmeester, an assistant professor in IBBME, was one of the capstone instructors at IBBME. He along with Profesor Chris Yip, who is appointed to the Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, the Department of Biochemistry and IBBME, have supported us through our journey, allowing us to tap into a variety of resources. We are also inspired by highly accomplished medtech innovators such as Professor Paul Santerre — he was an instructor of ours — and Dr. Brian Courtney, and the companies they have founded.

What’s next for this project?

Atto: We already have a provisional patent in place and we are working on improving our prototype and getting it to the point where we can test it in an animal model. Next, we want to form partnerships with major research institutes or hospitals, where we can do more pre-clinical research.

Is there hope to expand your line of products one day?

Atto: We’ve got many ideas! As we keep talking to surgeons, our plan is to develop a company with several products and solve clinical problems.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Exploring New Roads with Virtual Reality

Deep below street level, a state-of-the-art simulator gives University of Toronto researchers new insight into keeping drivers on the roads above safe.

DriverLab is the only simulator of its kind in Canada and offers a safe way to study a range of human variables in realistic traffic and weather conditions. It’s housed in the iDAPT Centre for Rehabilitation Research’s Challenging Environment Assessment Labs (CEAL) in the basement of Toronto Rehabilitation Institute.

An Audi A3 sits on a turntable in the centre of the simulator — a 6 metre-square sphere called a payload built on a hydraulic motion platform. Just like being on a real road, drivers using the simulator can feel bumps in the pavement or air turbulence from a passing transport truck. The car is surrounded by images cast by stereoscopic projectors that create driving scenarios from quiet residential streets to bustling highways and country roads.

The simulator is also the first in the world to offer realistic reproductions of headlight glare and rain. It can also mimic the experience of driving through ice and snow. Researchers can also program other obstacles into the simulation like a child running into the street.

“What we learn here could pave the way to help seniors maintain the ability to drive through something like a conditional license that would allow them to drive on city streets during the day. We’re also looking into whether cars should be equipped to recognize drowsiness in the driver and respond by turning the radio up or rolling down the windows to keep the driver awake,” says Geoff Fernie, a professor in the Department of Surgery and Toronto Rehabilitation Research Institute Director.

Researchers will also look to answer questions about the safety of driving while using medication — what dosages are safe and how much time needs to pass before someone gets behind the wheel?

Questions about the ways people interact with semi-autonomous vehicle features and driverless cars will be explored, too.

Most of what’s currently known about how different health conditions and circumstances affect driving has been done in a clinical setting. Road tests have traditionally been done on clear days in safe environments.

Fernie also says DriverLab also differs from other simulators because it was built specifically to test people, rather than to help car makers improve their designs or study the driving experience.

DriveLab is one of eight simulators at CEAL, which has a record of moving its research into the real world. The group often partners with existing companies and has also started its own companies to commercialize their innovations.

“Anything that gets the results of the research out so people can actually use it,” says Fernie who is also a member of the Graduate Department of Rehabilitation Science and is cross-appointed to the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering.

In 2015, a team studying stair safety in StairLab provided evidence used to change Canadian building codes.

Informed by findings from WinterLab, with its freezing temperatures, ice floor and tilting platform, CEAL researchers made a list of recommended winter boots last year — and changed Canadians’ footwear buying patterns.

“All the shoes we recommended were sold out by Christmas,” says Fernie. “This year, the retailers are coming to us to check their supplies before they put them on the market. We also have some new pairs of footwear being produced that are much better traction than they were last year.”

iDAPT includes scientists from a wide range of disciplines. About 60 per cent of its researchers are clinicians in specialities of every kind. Another third are engineers and computer scientists. The centre also attracts researchers in business studies and innovation management.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.