Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Siloes, status and silence: Study examines organizational factors around incivility in medicine

“We sought to understand the role that healthcare organizations might play in contributing to, and mitigating, toxic behaviours in the workplace within healthcare,” said Pattani, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and physician at St. Michael’s Hospital.

According to the study, nearly 60% of medical trainees report experiencing harassment or discrimination over the course of their education, and more than 30% of physicians say they are exposed to rude, dismissive or aggressive behaviour on a weekly basis.

Incivility in the workplace has a correlation with negative effects on the mental health of staff, as well as with productivity, team cohesion and organizational commitment. And the impact can be serious.

“Medicine is a work environment with heightened complexity involving the care of patients with acute or life-threatening conditions, so incivility may also have consequences for patient outcomes, ” Pattani said.

The researchers interviewed a diverse group of individuals from across the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto. All of the participants described collegial relationships with their colleagues, but they also all saw, heard of, or directly experienced uncivil behaviour.

Participants identified several organizational factors that contribute to incivility among physicians, including physician’s non-employee status in hospitals, departmental silos, poor leadership styles, a culture of silence and the existence of “power cliques.” They also suggested strategies to prevent, report and address incivility.

“The common themes that emerged included the need for the preservation of confidentiality; clearly articulated processes, defined and widely disseminated consequences with illustrative examples; as well as a rehabilitative approach for the victim and perpetrator of incivility,” said Straus, interim Physician in Chief at St. Michael’s and Division Director of Geriatric Medicine in the Department of Medicine

Existing strategies to influence behaviour in healthcare typically include feedback and awareness campaigns, which often focus on changing individual conduct rather than looking at the overall workplace culture.

“Although behaviour and individual personality may occasionally play a role, there may also be organizational factors that breed incivility, and this warrants further exploration,” said Straus.

In academic medicine, Pattani explained that trainees may have a more difficult time learning, or they may experience a loss of empathy towards patients and colleagues, as a result of burnout from working in a hostile environment.The researchers observed that burnout itself may contribute to an “incivility spiral,” suggesting that unprofessional behaviours may amplify the risk of further incivility.

They say that hospitals must work in tandem with the university to address this problem. Using this research, the department aims to develop a strategy to promote safe reporting, fair investigations and a rehabilitative approach to disciplinary actions.

Photo: Doctor by Hamza Butt via flickr

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Brianne Tulk

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Medicine by Design awards $1 million to advance new ideas in regenerative medicine

Three Faculty of Medicine researchers are among five U of T recipients of a 2018 New Ideas Award from Medicine by Design.

The awards, each worth $100,000 per year for up to two years, support innovative early-stage research that has the potential to make a significant impact on regenerative medicine research and translation.

As a 2018 awardee, Jane Batt, associate professor in the Department of Medicineand a respirologist at St. Michael’s Hospital,is investigating whether ultrasound-mediated gene delivery can help skeletal muscle repair itself after traumatic injuries that result in peripheral nerve damage. She is collaborating with Howard Leong-Poi, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine and head of the hospital’s Division of Cardiology.

Maryam Faiz, an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery, Division of Anatomy, has a New Ideas Award project to examine whether astrocytes — one of the most abundant cells in the central nervous system — can be reprogrammed to replace lost cells following stroke and ultimately restore cognitive function. She is collaborating with Cindi Morshead, Chair of the Division of Anatomy.

Maryam Faiz, an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery, Division of Anatomy, has a New Ideas Award project to examine whether astrocytes — one of the most abundant cells in the central nervous system — can be reprogrammed to replace lost cells following stroke and ultimately restore cognitive function. She is collaborating with Cindi Morshead, Chair of the Division of Anatomy.

Donna Wall, professor of Immunology and Paediatrics, will look at the impact of inflammation on the success of blood stem cell transplants, and whether patients experiencing inflammation due to infection or other immune responses need to undergo different preparation to reduce the risk of rejection. Wall is also section head of the Blood & Marrow Transplant/Cell Therapy program and a senior associate scientist in developmental and stem cell biology at SickKids. Her collaborators on this project are John Dick, professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics and a senior scientist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network; and Rebecca Marsh, clinical director of the Primary Immune Deficiency Program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“Through these New Ideas Awards, Medicine by Design is sowing the seeds of new discoveries and catalyzing innovation,” said University Professor Michael Sefton, executive director of Medicine by Design and a faculty member at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineeringand the Department of Chemical Engineering & Applied Chemistry. “These projects are high-risk, but they also have the potential to advance regenerative medicine in significant ways.”

The other recipients of a 2018 New Ideas Award are:

Paul Santerre, a professor at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineeringand the Faculty of Dentistry. He is developing nanoparticles to deliver genome-editing machinery to skeletal muscle cells, potentially opening up a new way to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Santerre is collaborating with Ronald Cohn, Chair of the Department of Paediatrics at U of T and Paediatrician-in-Chief at SickKids, and Anthony Gramolini, professor in the Department of Physiology.

And Melanie Woodin,who is a professor in the Department of Cell & Systems Biology. Her project involves repurposing chemogenetics — a tool scientists already use to study normal brain function — to target and regulate the activity of brain cells affected by ALS, creating the neurological equivalent of a remote control. Read more on Woodin’s research.

Medicine by Design selected these projects through a competitive, peer-reviewed process. This is the fifth time Medicine by Design has awarded New Ideas funding. Learn about previous New Ideas projects.

Medicine by Design also supports 19 collaborative team projects that are accelerating regenerative medicine discoveries in a variety of disease areas, including heart failure, diabetes, and neural diseases. Building on decades of made-in-Toronto discoveries, Medicine by Design is developing new peaks of excellence and strengthening Canada as a global leader in regenerative medicine thanks to a $114-million investment from the federal government’s Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

With thanks to Ann Perry, Medicine by Design

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Avoiding Catastrophe: Yeast Study Reveals Clues to Maintaining Genome Size

Led by Tina Sing, a PhD student in Professor Grant Brown’s lab in the Donnelly Centre and Department of Biochemistry, the study’s findings are published in The Journal of Cell Biology.

Brown likens the genome to an instruction book organized into a set number of chapters, or chromosomes. “It’s important that the number of chapters stay constant,” he says. “It would be bad if you lack instructions for certain processes but surprisingly it’s also bad if you have too many instructions.”

Having an extra copy of chromosome 21 leads to Down syndrome, while an absence of one X chromosome will turn females sterile as seen in Turner syndrome. In cancer cells, whole genome duplication followed by haphazard chromosome loss allows tumour cells to accumulate genes which help them outgrow healthy cells.

“When a cell makes a decision to divide it needs to make sure its DNA is equally segregated between both daughter cells,” says Sing, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. “The cells must first replicate their DNA and then they have to pull apart these two copies of the DNA so that each daughter cell receives one complete copy of the entire genome.”

Sing uncovered a new role for a known protein machinery called RSC, for “remodels the structure of chromatin” and pronounced as “risk”, in helping separate the duplicated chromosomes equally between daughter cells. RSC does this by helping the formation of the centrosome, a structure that sprouts tiny filaments which grab each set of chromosomes and pulls them apart. “We found that if cells lack RSC function then this causes abnormal DNA segregation and a spontaneous doubling of chromosome number in cells,” says Sing.

In their experiments, Sing and Brown used budding yeast—the same single-celled microbe that helps bread rise and beer ferment—which showed uncanny resemblance to cancer cells when RSC is no longer working. Besides having a higher number of chromosomes, yeast cells lacking RSC function also have more centrosomes. Whereas heathy cells typically have two centrosomes during cell division, RSC mutants often had many more, making it difficult for them to segregate their chromosomes properly.

Previously, RSC was known for its role in switching genes on and off. Sing’s finding that RSC is also important for DNA segregation was unexpected and ties together with previous findings from other labs to potentially help explain how a form of childhood cancer develops.

Mutations in the human version of RSC also lead to spontaneous increase in chromosome number and have been found in rhabdoid tumours, a highly aggressive form of kidney cancer. Also, if mouse cells lose RSC function, they can turn cancerous. However, there was nothing known about RSC that would suggest its involvement in chromosome segregation. Now, thanks to the insights from yeast cells, it is possible that RSC has a similar role in humans.

“It’s always surprising to think about how fundamental processes in yeast also take place in humans,” Sing says. “We think that our study gives some insight into this observation in cancer cells and we think it’s possible that this complex is also helping with chromosome segregation in human cells.”

Sing’s finding was serendipitous. When she started working on RSC, her goal was to dig deeper into some of its more conventional roles. It was only after she repeatedly noticed that cells lacking RSC function had twice the normal number of chromosomes that she realized she was onto something unexpected. “The increase in chromosomes was more interesting than what we were looking for,” she says. “I think the study is a good example of how sometimes when you set out to study a specific biological problem you can be surprised by the data that you find and sometimes just following your curiosity down a different path can lead to understanding another aspect of biology.”

The research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Jovana Drinjakovic

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.University of Toronto Remembers Professor Jack Tu

University of Toronto faculty, students and staff are mourning Prof. Jack Tu, an internationally-renowned cardiologist and professor in both the Department of Medicine and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, who passed away on May 30.

“The University of Toronto has lost a dedicated mentor and friend,” says Trevor Young, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. “A tireless researcher and clinician scientist, Jack made significant contributions to measuring and improving the health and quality of care for Canadians with cardiovascular diseases.”

Tu was a world expert in medical epidemiology and health services research. His research advanced knowledge in critical areas of healthcare and had a tremendous impact on the healthcare system and patients.

“It is because of his research that we now know that where someone lives can have an impact on their cardiovascular health,” says Andy Smith, President and CEO of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre where Tu was a staff physician and senior scientist. “It is because of his research that we now know that ‘good’ cholesterol is not an effective marker for heart health. It is because of his research that there is now a tool to predict mortality in patients who present with heart failure in the emergency room.”

In 1996, Dr. Tu was appointed assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at University of Toronto, the same year he joined Sunnybrook as a staff physician in the division of internal medicine. He became a scientist in Evaluative Clinical Sciences and the Schulich Heart Program in 1999. He joined the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) as a scientist in 2000, where he led the cardiovascular and diagnostic imaging research program.

In 2004, he was promoted to professor in both the Department of Medicine and at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation at U of T and to senior scientist at ICES. Two years later, in 2006, he became a staff physician in Sunnybrook’s Schulich Heart Centre. Across all these years and as an integral, highly respected member of all these families, he enriched many lives as a physician, researcher, mentor, colleague and friend.

“Jack was a giant in health services research, and a great teacher and mentor to our students,” says Adalsteinn Brown, Interim Dean of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Dalla Lana Chair in Public Health Policy. “He was constantly searching for innovative ways to improve the health system and the quality of health care for Canadians. His dedication to our field and his scholarship will be greatly missed.”

“Jack’s dedication to his work and contributions to the research community and the health outcomes of Canadians is undeniable,” adds Gillian Hawker, Chair of the Department of Medicine at U of T.

Tu held a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research and published over 300 peer-reviewed journal articles in several highly ranked publications including The New England Journal of Medicine, Journal of the American Medical Association and Annual of Internal Medicine. A prolific researcher, he published more than 130 articles in peer-reviewed journals in the last five years alone.

Tu held several research grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation and was the team leader of the CIHR-funded Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team (CCORT), which links a network of over 30 leading cardiac outcomes researchers across the country. In 2015 Tu received Department of Medicine Researcher of the Year Award. In addition to his extensive research activities, Tu also supervised students at all levels of training and lectures extensively across the world.

With files from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Brianne Tulk

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Could the Brain’s Frontal Lobe Be Involved in Chronic Pain?

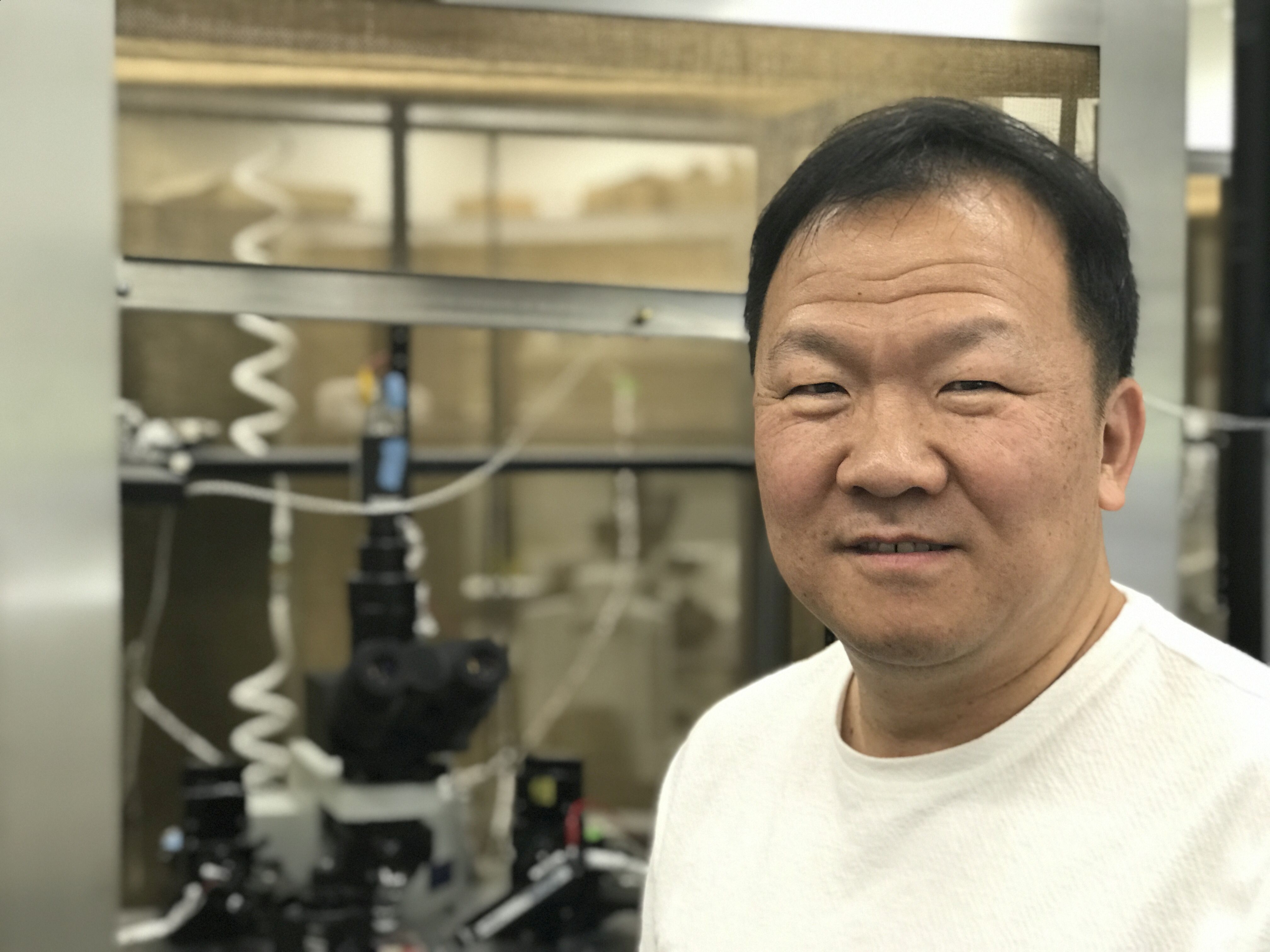

A University of Toronto scientist has discovered the brain’s frontal lobe is involved in pain transmission to the spine. If his findings in animals bear out in people, the discovery could lead to a new class of non-addictive painkillers.

For 20 years, Min Zhuo, a professor of Physiology in the Faculty of Medicine, has been intrigued by invisible pain; in particular, chronic pain with no obvious cause. He has long suspected that the standard way of viewing spinal pain – it must come from injury or tissue inflammation – and the usual understanding of how to treat it – block it from entering the spinal cord – wasn’t telling the whole story.

Now, Zhuo has demonstrated in mice and rats that some spinal pain actually begins in the brain’s frontal lobe, an area previously thought to be uninvolved. And he has shown how treating the pain in this area could be effective at preventing chronic pain. Zhuo published his results May 16 in the journal Nature Communication.

“When doctors can’t see anything wrong to cause chronic pain, often they think patients are making it up,” says Zhuo. “But pain that originates in the frontal lobe would be very different from pain that comes from a physical injury, like a herniated disc. There wouldn’t necessarily be any injury to see. That’s because our personality and emotions live in this region. If the frontal lobe can produce physical pain, that pain would be deeply tied to emotions like anxiety.”

Scientists already knew that the prefrontal cortex was in some way involved in pain because it would light up in scans of people in pain. But that activity was always thought to be symptom not cause, says Zhuo.

“When you have extreme anxiety, more neurotransmitters are released that end up causing pain in the spine,” he says. “Normal functions like walking shouldn’t be painful. But this flood of neurotransmitters sends the spine into hyper drive, and it starts treating ordinary sensations like pain. That could explain why anxiety can cause chest pain and make you think you’re having a heart attack. Or why some people experience pain when you touch them. I believe this helps to explain why emotional pain causes physical pain.”

The good news is that pain from the frontal lobe seems to be transmitted in a simple, direct way to the spine – making it relatively easy to shut down. Neurons in the frontal cortex send signals all the way down the spinal cord, says Zhuo, whereas pain signals from other areas of the brain are mediated by a complex network.

In animals, Zhuo found that pain was associated with increased neurotransmitters released from the frontal cortex. He was able to lessen pain by reducing the amount released. His next step is to test this process in people.

Those who suffer from anxiety along with neuropathic pain would likely benefit from a painkiller targeting the frontal lobe, says Zhuo.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Heidi Singer

Error message

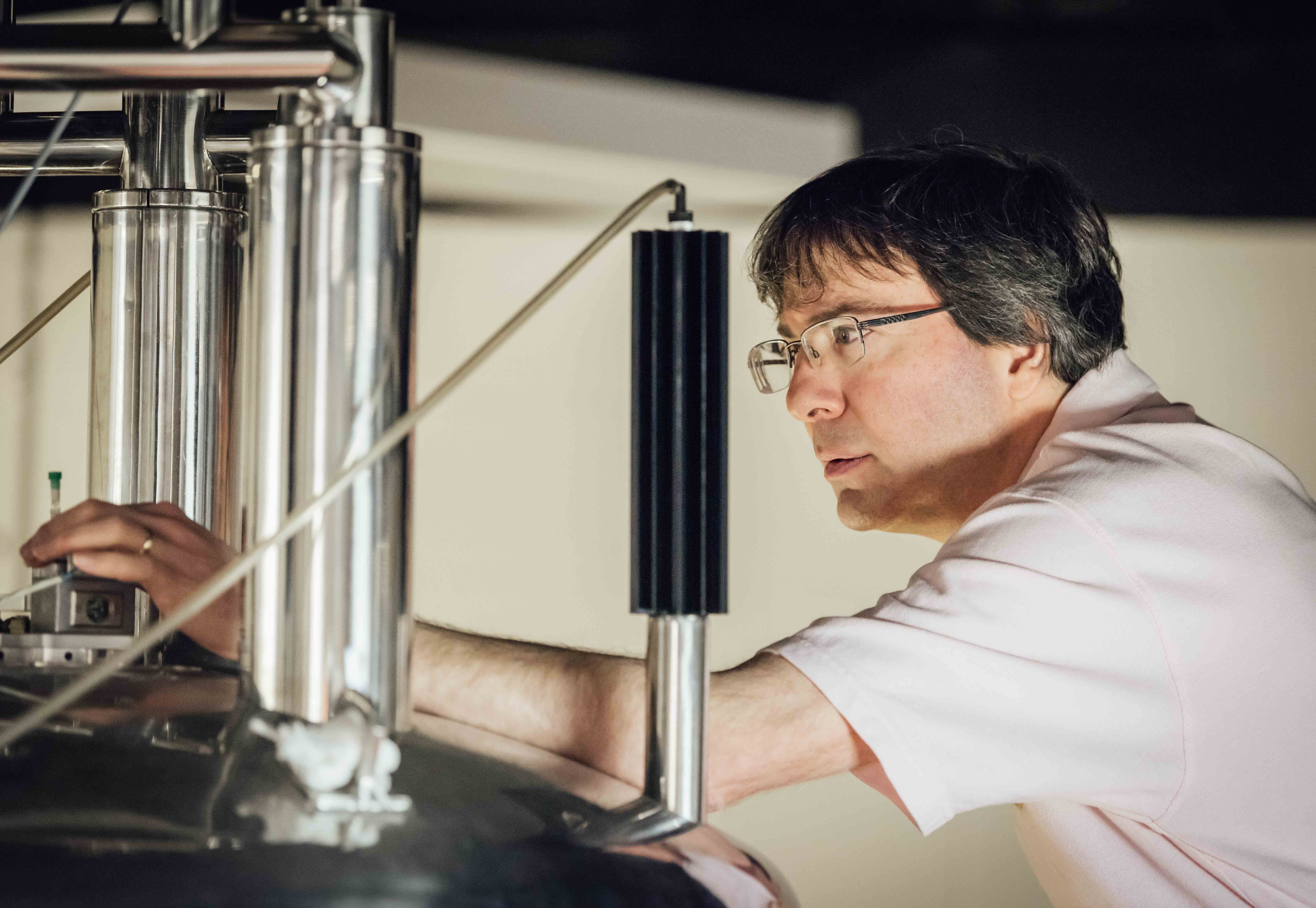

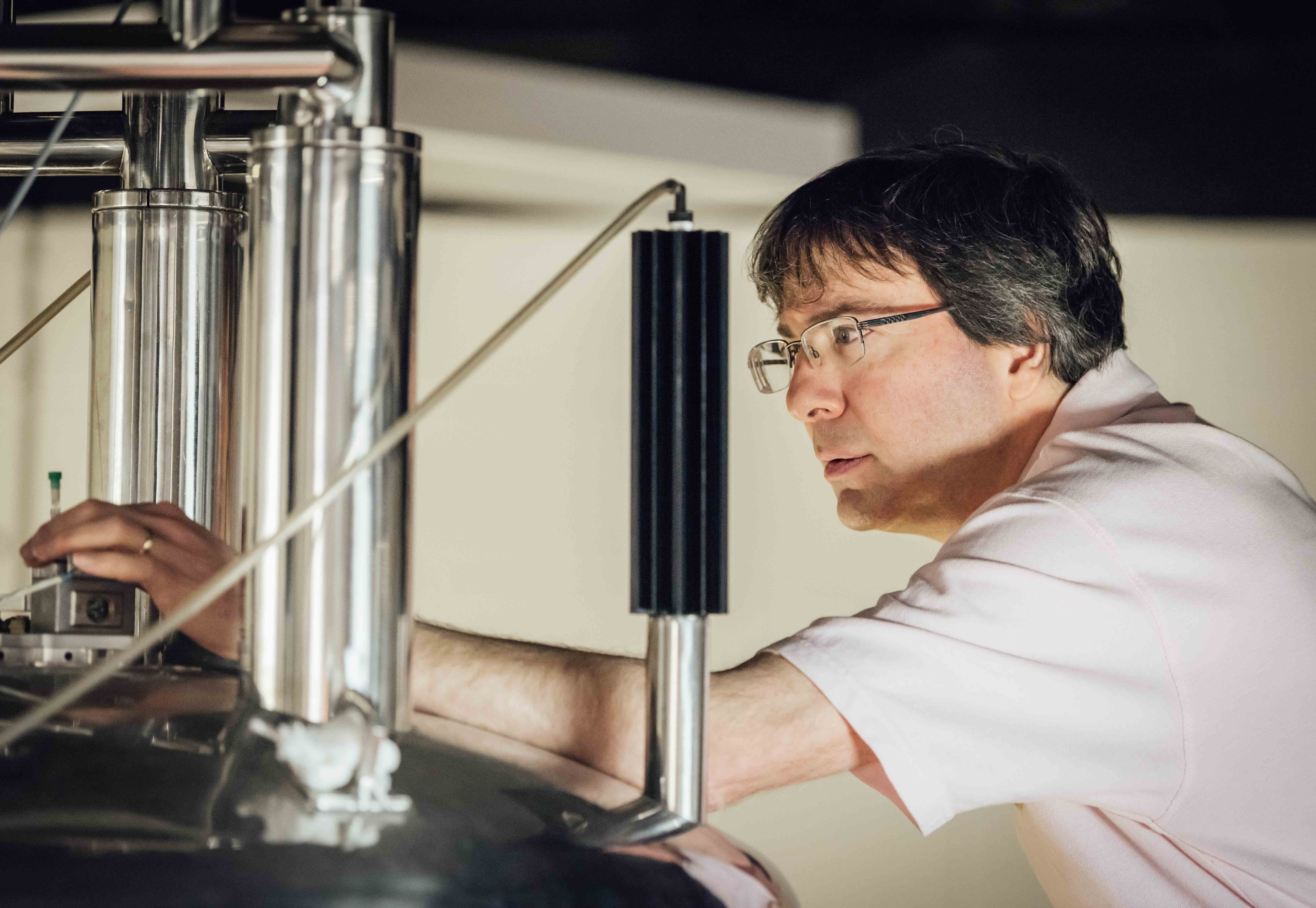

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Million Dollar Prize for Scientist Lewis Kay

The prize recognizes Kay for his work advancing nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The technology helps scientists capture images of the proteins within human cells to explore their structure and behaviour. As he does his ground-breaking research, Kay also takes an open-access approach to science, which allows investigators around the globe to use his methods.

“It is an honour to receive the NSERC Herzberg Gold Medal in recognition of my NMR spectroscopy research,” says Kay. “With the support of my colleagues at the University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children, and the generosity of the Government of Canada, I’ve been able to attract a team of talented individuals to my lab. With this award, we’re going to continue to do what we do best: listen to what the molecules are trying to tell us.”

In addition to being presented with the medal in Ottawa, Kay will receive funding of $1 million over five years for discovery research.

Among the proteins Kay’s lab examines is an enzyme associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a degenerative disease that causes a person’s muscles to break down over time, leading to the loss of their ability to move and ultimately, breathe. Mutations in this enzyme are present in nearly 20 per cent of people with an inherited form of the disease. By seeing how the enzyme’s molecules fold and unfold, researchers can work to understand how to prevent or fix the mutations.

The Herzberg gold medal is the highest honour given by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). This annual award celebrates sustained excellence and overall influence of research work conducted in Canada in the natural sciences or engineering. It’s named for Canadian Gerhard Herzberg, who was honoured with the 1971 Nobel Prize in Chemistryfor his contributions to the knowledge of electronic structure and geometry of molecules, particularly free radicals.

Previous winners from U of T include:

- Stephen Cook, Computer Science and Mathematics (2012)

- W. Richard Peltier, Physics (2011)

- Geoffrey Hinton, Computer Science (2010)

- John C. Polyani, Chemistry (2007)

- Richard Bond, Theoretical Astrophysics (2006)

- James Arthur, Mathematics (1999)

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Erin Howe

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.U of T Team Develops the First Smartphone Visual Field Test

A University of Toronto team led by Professor Moshe Eizenman has developed a simple, inexpensive way for people to test their own vision for early signs of glaucoma.

Using a smartphone, and a $25 virtual reality device called Google Cardboard, patients can quickly and easily monitor their peripheral vision for free, rather than visiting a clinic.

This is especially important in areas in Asia, India, Nepal and West Africa, where 90% of all glaucoma goes undetected, and is typically only discovered after it causes permanent vision damage, says Eizenman, a professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences and the Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering (IBBME).

“Visual field testing on personal smartphones can enable vision screening in developing countries where access to expensive equipment and dedicated testing facilities is limited,” he says. “This is crucial in remote areas where travel time to central testing facilities is prohibitively long or expensive.”

Working with Bill Shi, a third-year undergraduate engineering student at U of T, and ophthalmology professors Yvonne Buys and Graham Trope, the team tested 19 patients using both the mobile device and a traditional visual field testing instrument. The results between the two testing methods showed good agreement.

Eizenman also predicts his invention could help improve the management of open angle glaucoma, where frequent testing is recommended. Despite the potential benefits of frequent testing, patients with glaucoma are usually elderly and have a hard time following through.

Eizenman presented his findings at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology on May 1.

The next step is for Eizenman and his team to test the utility of their visual field testing technology in parts of the world where glaucoma goes undetected, starting with India and Nepal.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Heidi Singer

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Faces of U of T Medicine: Sujen Saravanabavan

Sujen Saravanabavan is passionate about helping others. In addition to his medical studies, the third-year student is also an active member of various student leadership groups. This weekend, he’ll be presented with an MD Financial Management Student Leadership Award at the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS) Spring General Meeting in Halifax. The award recognizes medical students who have made innovative contributions to their schools and communities. He recently told writer Erin Howe about his volunteer work and plans for the future.

You’re the senior U of T representative for the CFMS, a member of the executive committee for Ontario Medical Students Association and you’ve also been the Vice President of External Relations for U of T’s Medical Society. What have you enjoyed about taking on these kinds of roles?

I had the opportunity to be Vice President External for my first two years of medical school. It was one of the most rewarding and challenging experiences of my time as a pre-clerk. I loved working with passionate colleagues, the process of understanding what advocacy means to me personally and seeing a vision through to completion. One example is starting the Toronto Political Advocacy Committee through the Medical Society, which ended up doing some great work in the City of Toronto.

How will these roles help you prepare for your career?

I spent a lot of time deepening my understanding of what advocacy means to me and what types of roles I’d like to take on in the future. Through this experience and others, I’ve become passionate about the social determinants of health. I hope to have a career that involves clinical medicine, policy and advocacy and this creates a strong foundation and perspective.

What have been the best parts of clerkship so far?

There have been many amazing things about clerkship! The best parts have been the moments when I feel I’m positively impacting a patient’s life. In one experience, I worked with a patient who had a particularly challenging social circumstance, which included living in a shelter. Through our encounter, I realized he had a wealth of ideas to support others in similar circumstances. I encouraged him to write a letter to his local government official to express his ideas and concerns. Together, we found his city councillor and created a plan for the patient to write a letter to them. I didn’t have the opportunity to follow-up with him, but before leaving that appointment the man thanked me for believing in him. I like to think he actually wrote that letter and that this experience helped encourage him.

I’ve also enjoyed the personal growth that happens as a clerk. Don’t get me wrong — it’s also the most challenging part. Being constantly evaluated both clinically and through testing can lead to many emotionally challenging situations. But constantly being pushed to your limits made me better. It’s pretty rewarding to get at least some of the questions your senior asks correct!

Where do you see yourself in 15 years?

I’m interested in pursuing something where I work with children, both clinically and in terms of my advocacy. I’d also love to be involved in teaching future medical students. While work is important to me, hopefully I’m balanced in terms of my personal life. I really want to have a family and maintain the friendships I’ve made so far.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

I wish I had something that makes me look incredibly smart and thoughtful, but I honestly love playing video games. I also really enjoy practicing close-up magic (something I hope to incorporate into my clinical medicine) and spending time with my friends.

You also help teach dance to kids with autism — can you tell me more about this?

I first learned to dance — specifically popping, clown walking and tutting — when I was fourteen by watching YouTube videos. I had no idea it would lead to helping teach a dance class many years later! I did this for nearly two years during my pre-clerkship years. There are so many things I loved about this experience. Teaching children with autism was a learning experience for me, but the part I enjoyed the most was simple — just watching the kids have fun with dance. Kids find pleasure in such simple things. Seeing them engage with dance and witnessing dance bring them closer to each other and their families was incredible!

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Medical Students March For a Permanent Fix to Residency Shortages

Dozens of medical students from U of T and across the province gathered at Queen’s Park on April 25 to press political leaders for a long-term solution to the lack of residency spots for graduating medical students.

Although 92 per cent of U of T medical students matched to a residency position across the country this year, medical students face a chronic shortage of positions due to cutbacks. After intense lobbying this spring by U of T and other medical school leaders and students, the Ontario government recently agreed to provide $23 million to offer a residency spot to all 53 Ontario medical students who are currently unmatched to a residency position. Now, students and medical school leaders are looking for a permanent solution.

“We were very excited about the announcement but it’s important to note this is a one-time solution,” said Victoria Reedman, a march organizer and 2nd year medical student at U of T. “It will clear the backlog for this year but it doesn’t solve the problem long-term.”

To become a practicing physician in Canada, medical school graduates must complete a residency program. At the end of their fourth year of “undergraduate” medical training, graduating students apply to a postgraduate residency program, such as family medicine, psychiatry or surgery. But due to cuts in residency spots, particularly in Ontario, the number of unmatched students has grown in recent years.

To fix the problem, students want the government to create more residency spots, but also to leave room in the budget to offer flexible spots each year for those students who might not match, said Kayla Sliskovic, president of U of T’s student-run Medical Society. And many are calling for an overhaul to the Canada-wide matching system, which they call outdated.

Students were relieved to learn about the temporary fix earlier this month, Sliskovic said, but “the worry, the concern, the stress is still there.”

Representatives of all three major Ontario political parties spoke at the student’s rally, and organizers read statements from non-matching students. Professor Patricia Houston, U of T’s Vice Dean of the MD Program, thanked the Ontario government for its quick action to fix this year’s shortage, and told the students, “I’m right there behind you!

“You deserve to have a residency spot,” she said to the marchers. “The number of unmatched medical students has tripled in the last three years. This is a system problem, it can’t be your problem. We have to find a solution and that is why we’re here today. I know that if we all work together collaboratively and creatively we will find a way forward.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Heidi Singer

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.Strong First Step for Ontario’s Unmatched MD Grads

The Ontario government, working with U of T’s Faculty of Medicine and other health leaders, has taken a strong first step to address the growing shortage of residency positions for medical school graduates. The province announced today it will create more residency spots this upcoming academic year for graduates who did not get a residency position in the current match. The goal is to offer a spot to all 53 currently unmatched Ontario medical students.

The Ontario government, working with U of T’s Faculty of Medicine and other health leaders, has taken a strong first step to address the growing shortage of residency positions for medical school graduates. The province announced today it will create more residency spots this upcoming academic year for graduates who did not get a residency position in the current match. The goal is to offer a spot to all 53 currently unmatched Ontario medical students.

The province is investing up to $23 million over six years to create opportunities for these unmatched MD grads to train in family medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, paediatrics and psychiatry. Graduates in the new residency spots will be required to provide service after residency for two years in underserviced communities across the province - for instance, specific regions in Northern Ontario.

“By funding more residency opportunities in the province, our government is ensuring access to care in the areas where Ontarians need it most and supporting medical students in achieving their potential,” said Dr. Helena Jaczek, Minister of Health and Long-Term Care. “This forward-looking investment is yet another way we are providing high-quality health care, closer to home.”

To become a practicing physician in Canada, medical school graduates must complete a residency program. At the end of their fourth year of “undergraduate” medical training, graduating students apply to a postgraduate residency program, such as family medicine, psychiatry or surgery. But due to cuts in residency spots, particularly in Ontario, the number of unmatched students has grown in recent years.

Although 92 per cent of graduating students at U of T matched to a residency position this year, longer-term plans are still needed to ensure Ontarians are well-served and medical students can effectively plan for their futures. U of T’s Dean of Medicine praised today’s announcement as an excellent first step.

“The Government of Ontario heard the voices of our medical students loud and clear – and we’re very pleased to see an immediate action plan in place for all unmatched students in Ontario,” said Professor Trevor Young, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Co-Chair of the Council of Ontario Faculties of Medicine. “We very much appreciate the support of Minister Jaczek and look forward to working collaboratively to create a sustainable long-term plan that meets the needs of patients of Ontario as well as our students.”

U of T medical students have been working hard with others across the province to raise awareness of the problem, with visits to Queen’s Park officials and ongoing advocacy. “We welcome this clear commitment to ensuring a residency spot for every graduating medical student in the province,” said Vivian Tam, of the Ontario Medical Students Association. “We look forward to further action to ensure our physician services planning system is robust, transparent, and based on patient need.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Heidi Singer